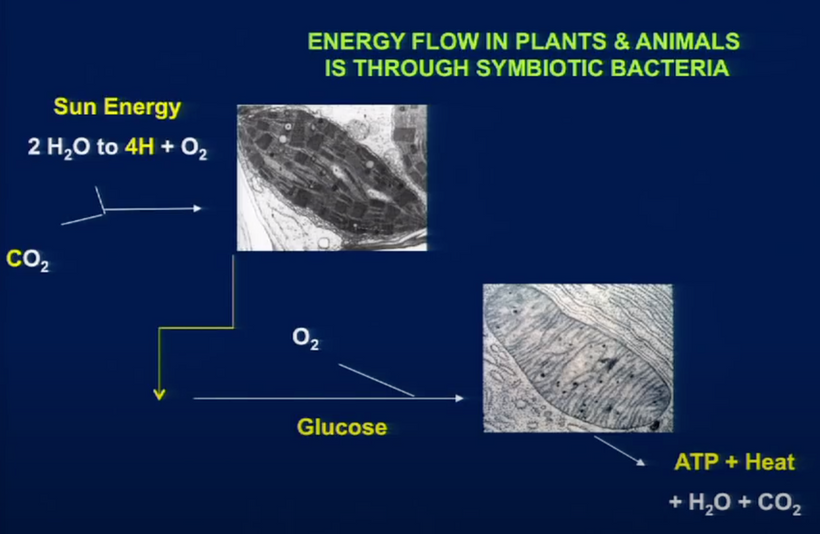

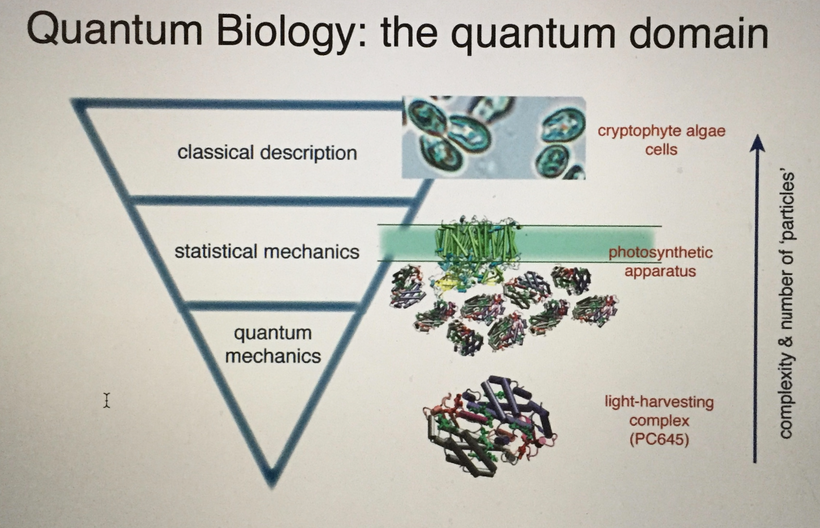

Organisms are open thermodynamic systems dependent on energy flow. Energy flows in together with materials, & waste products are exported, along with the spent energy that goes to make up entropy. Entropy defines the flow of time. Molecular clocks are flowmeters of entropy. And that is how living systems can, in principle, escape from the second law of thermodynamics by staying on the edge of it. Cells do this by creating order from chaos using cells as a dissipative structure. That structure is built around the AMO physics of atoms in cells. Their molecular arrangement is key. This mimics what silicon valley engineers do to silicon in a semiconductor fabrication plant when they build solid-state circuits. Semiconductors use electric power and make light. Cells do the same.

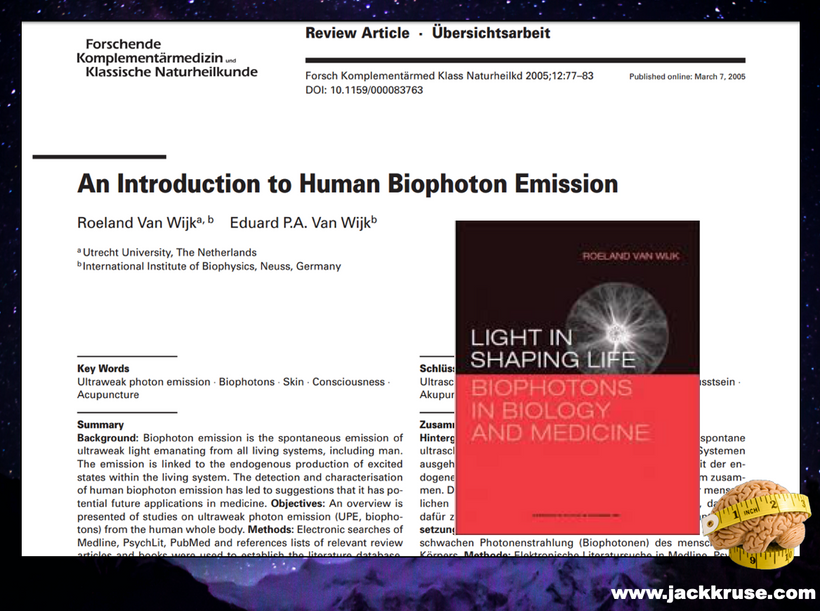

Breath work essentially controls the band gap changes in our semiconductors because of how powerful the reaction is in turning 02 into H20 in our mitochondria. A change in oxygen saturation is capable of changing the color of light which changes the frequency of the light frequencies of the light emitted as biophotons. Breathwork is about changing the frequencies of biophotons so you can imprint changes onto to tissue where wide band semiconductors are found. This is how light sculpts mammalian semiconductors from an evolutionary perspective. But our story does not begin with mammals. It begins with the earliest forms of life on Earth. Bacteria and Archea.

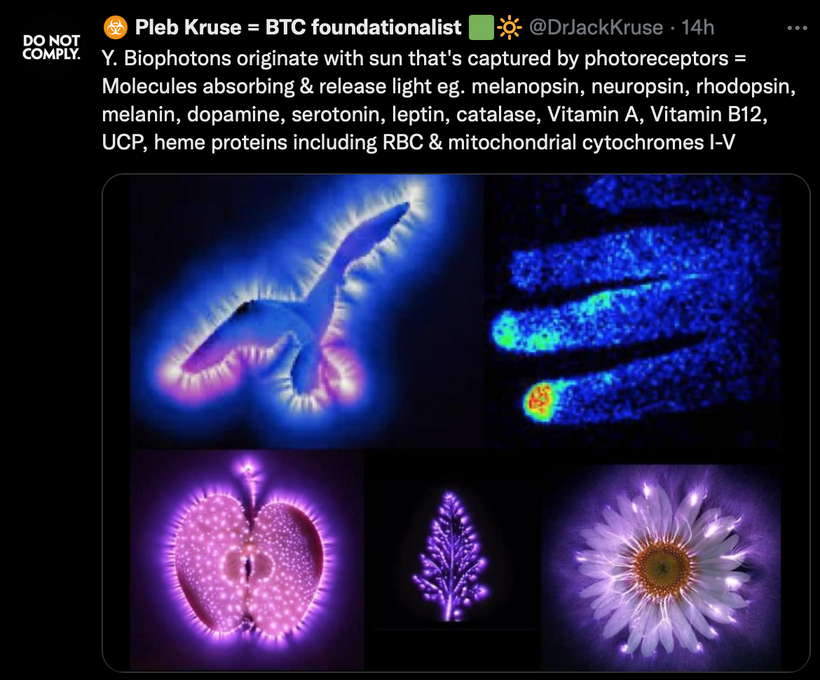

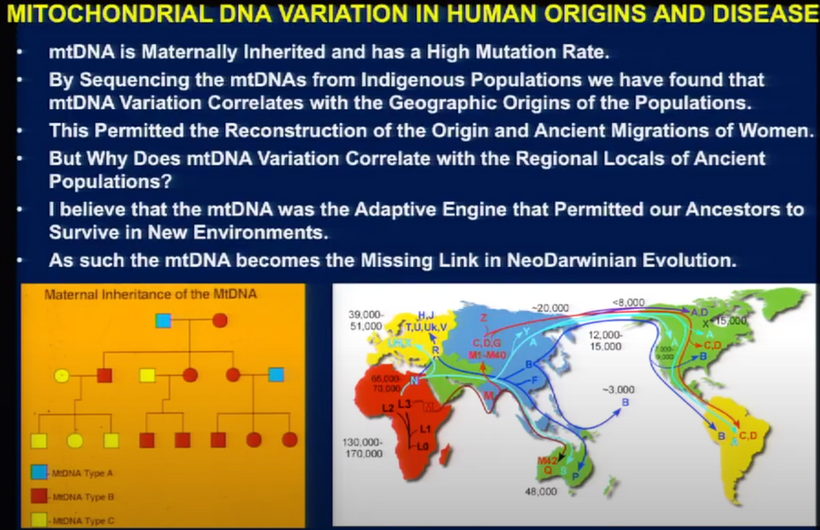

According to the domain system in evolution, the tree of life consists of three domains such as Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukaryotes. The first two are all prokaryotes, single-celled microorganisms without a membrane-bound nucleus. All organisms that have a cell nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles are included in Eukaryotes. Every domain of life emits light from their cells. Prokaryotes emit 5000 time more light than eukaryotes do. Semiconduction is the the reason why this happens.

HOW DID THIS SEMICONDUCTIVE PLAN GET SCULPTED BY EVOLUTION?

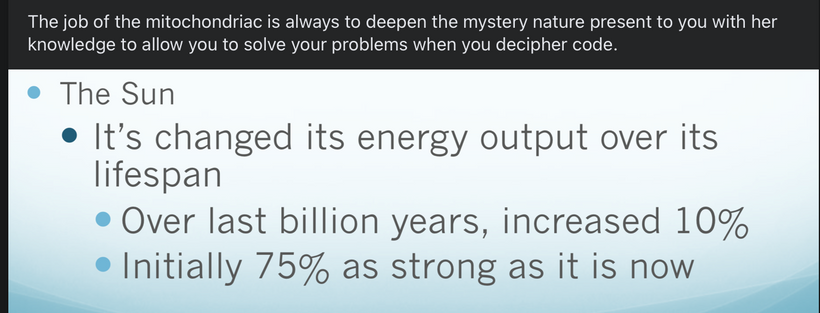

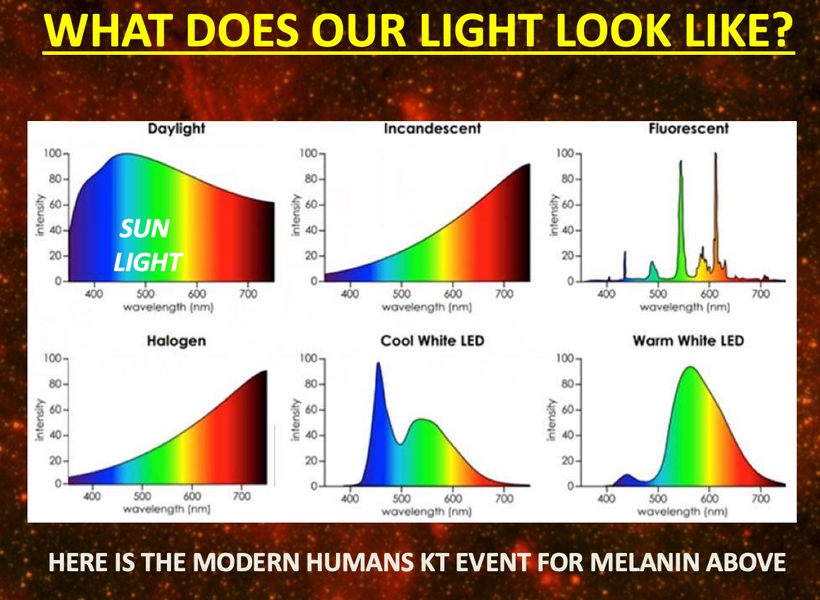

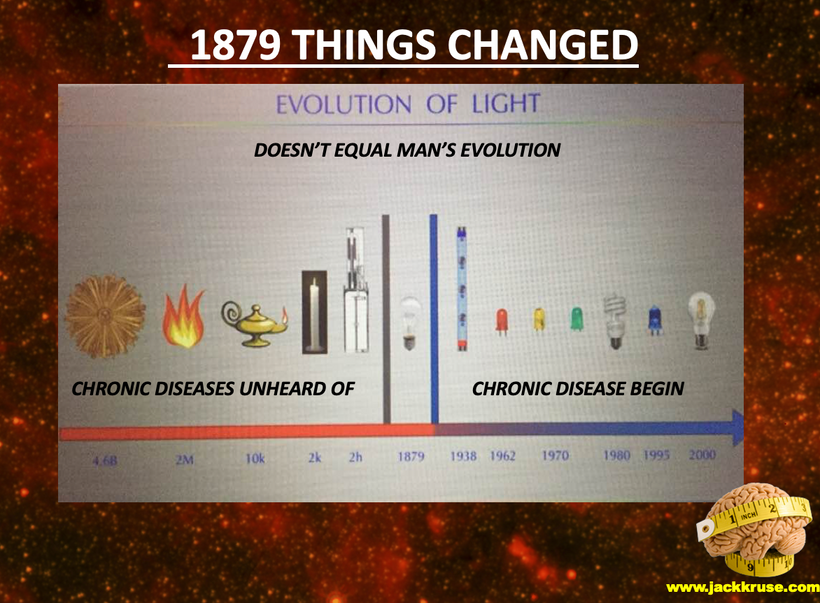

The frequency of light changed for life many times in our evolutionary history.

We are so acclimatized to the presence of oxygen on our planet Earth, that we take it for granted. However, oxygen was absent from the earth’s atmosphere for close to half of its lifespan. When the earth was formed around 4.5 billion years ago, it had vastly different conditions. At that time, the earth had a reducing atmosphere, consisting of carbon dioxide, methane and water vapor, as opposed to the present-day atmosphere that consists primarily of nitrogen and oxygen.

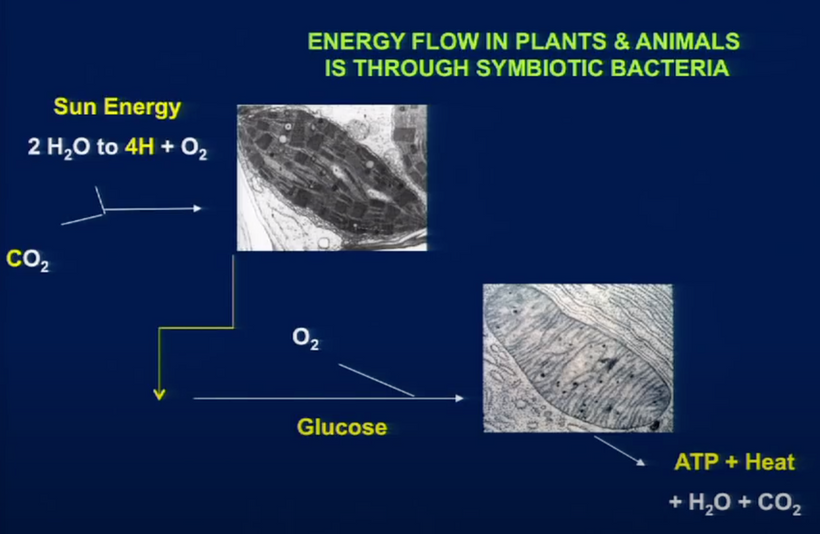

Though sunlight split the water vapor in the atmosphere into oxygen and hydrogen, the oxygen quickly reacted with methane and got locked into the earth’s crust, barely leaving any traces in the atmosphere. A silent, mysterious force worked to release oxygen steadily, until the very composition of the atmosphere changed. That mysterious entity happened to be a microbe: Cyanobacteria.

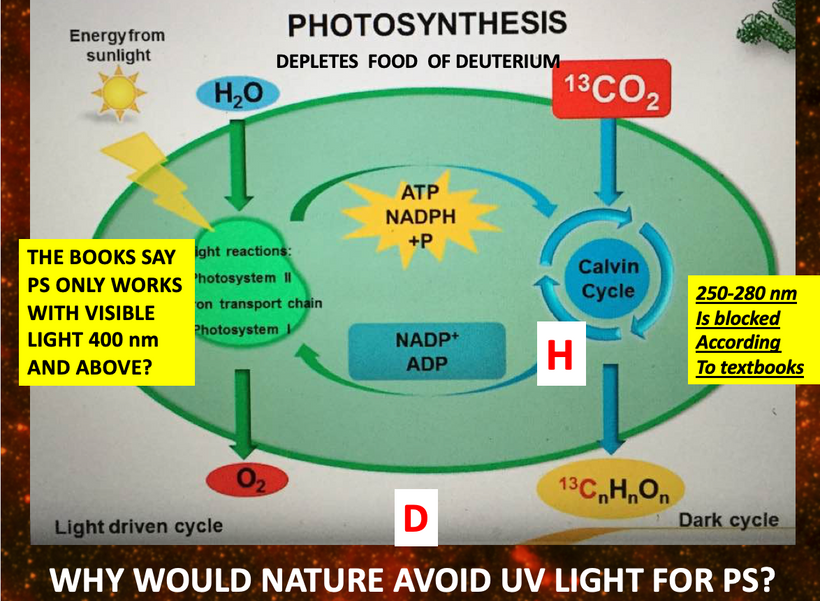

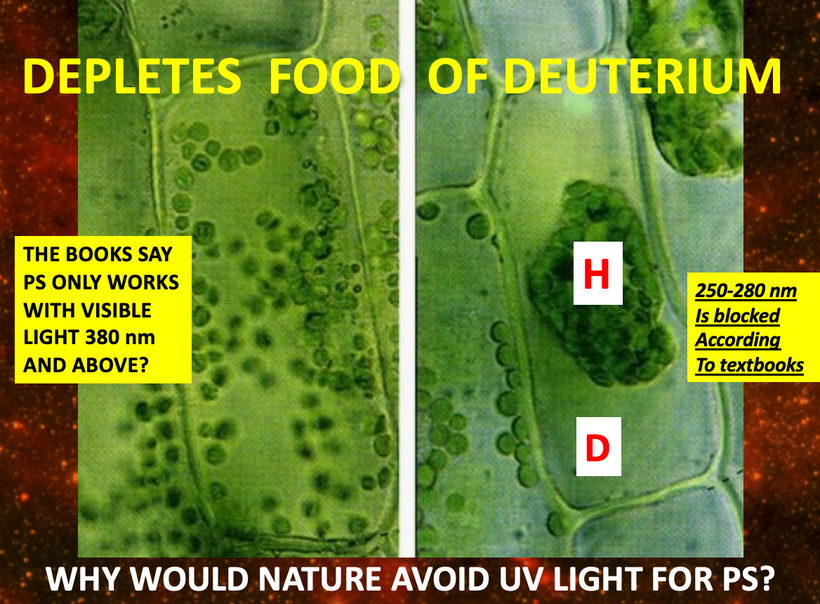

The earliest onset of life on our planet occurred around 3.8 billion years ago. Since oxygen was projected to be absent from the earth at that time, metabolism in living organisms would have been anaerobic, involving the use of minerals present in the ocean to generate energy. However, around 2.7 billion years ago, a peculiar group of microbes, known as cyanobacteria, evolved. Phylogenetic analyses based on 16S and 23s rRNA, genome reconstructions and fossil evidence have been used to understand the evolutionary characteristics of these early living organisms. These microbes possessed the remarkable ability to perform photosynthesis, (i.e., they could generate energy from sunlight). Cyanobacteria possessed the machinery to utilize water as a fuel source by oxidizing it. More significantly, the by-product of photosynthesis happened to be oxygen.

Among all the biochemical inventions that life could conceive, the ability of cyanobacteria to utilize water as fuel for oxygen generation must rank as one of the most ingenious. Trust me there are few more in this blog.

Researchers have guessed that the levels of oxygen released into the seawater by cyanobacteria gradually increased over time, and that over a span of 200-300 million years, oxygen was produced at a faster rate than it could react with other elements or get sequestered by minerals. The oxygen released by cyanobacteria steadily accumulated over vast swathes of the ocean and oxygenated the water. Gradually, the accumulated oxygen started escaping into the atmosphere, where it reacted with methane. As more oxygen escaped, methane was eventually displaced, and oxygen became a major component of the atmosphere.

This event, known as the “Great Oxidation Event,” occurred sometime between 2.4 – 2.1 billion years ago. Life remained simple with just bacteria and archea dominated the planet. Then environmental change happened again on Earth.

Our star went through puberty so to speak, as most G class stars do, and began transforming energy to make about 10% more UV light than normal. This increases in Oxygen did something else; our weather changed as accumulation of oxygen in the atmosphere got pronounced. In fact, we know it led to one of the earliest ice ages on earth.

Methane is a greenhouse gas, since it traps heat from sunlight and warms the planet. As methane was displaced by oxygen, global temperatures cooled sufficiently to generate ice sheets that extended all the way from the poles to the tropics. That temperature change has a massive effect on how semiconductors operate.

Temperature affects semiconductors band gap size too. Cooling increases band gap size. More on that soon.

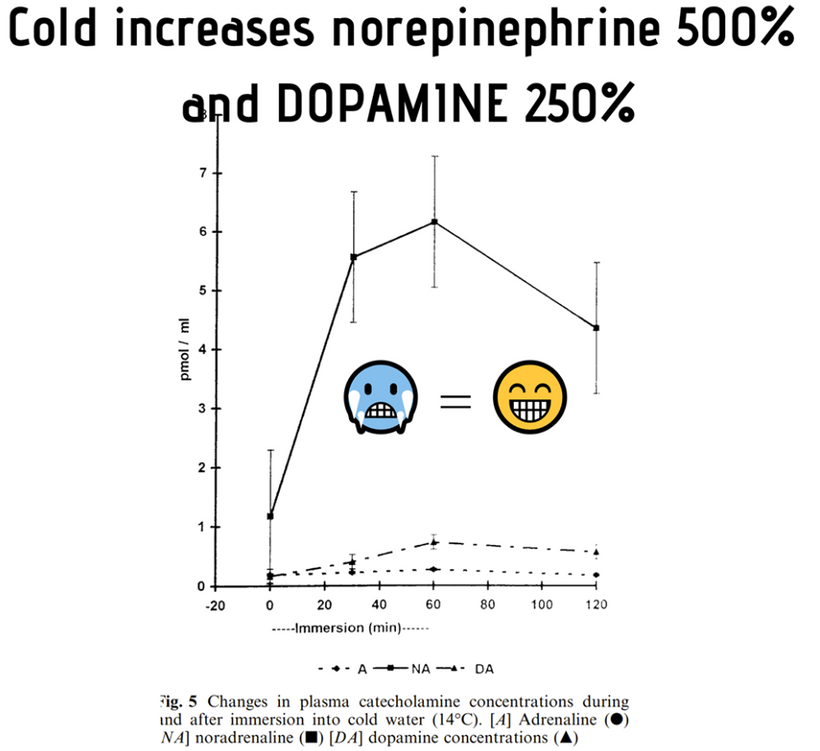

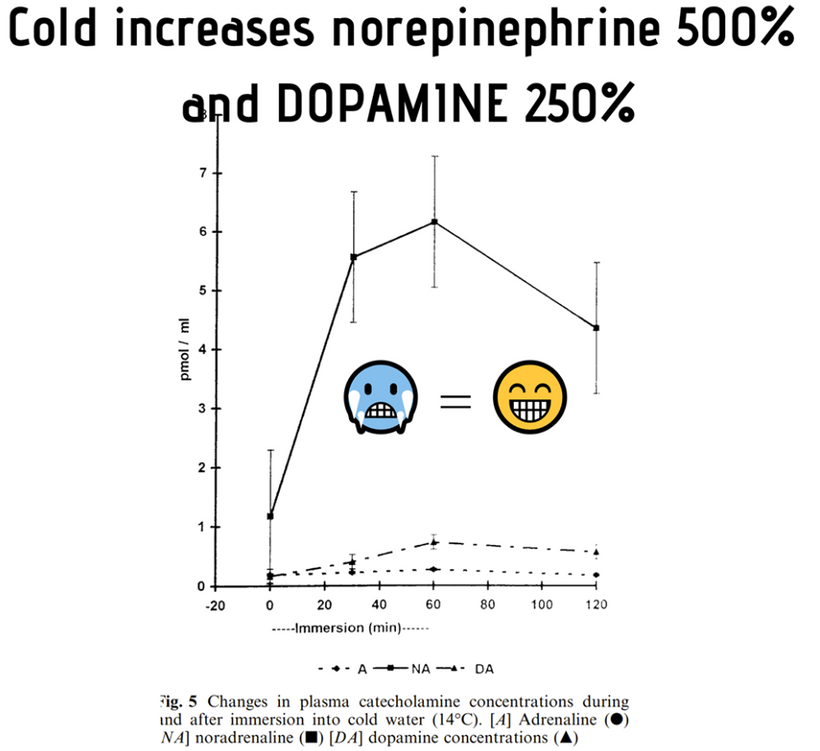

Cooling gave us evolutionary pressures to create catecholamine chemicals in prokaryotes like dopamine and adrenaline using a new semiconductive protein inside cells.

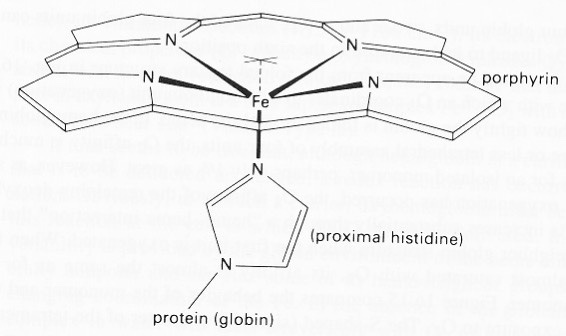

A lack of oxygen affected the early oxygen carrier molecules called heme proteins.

Initial oxidation of hemoglobin to the ferric (Fe3+) state without oxygen present converts hemoglobin into a useless “hemiglobin” or methemoglobin, which cannot bind oxygen. Methemglobin is an ancient protein used by life long ago when oxygen was not prominent in our atmosphere.

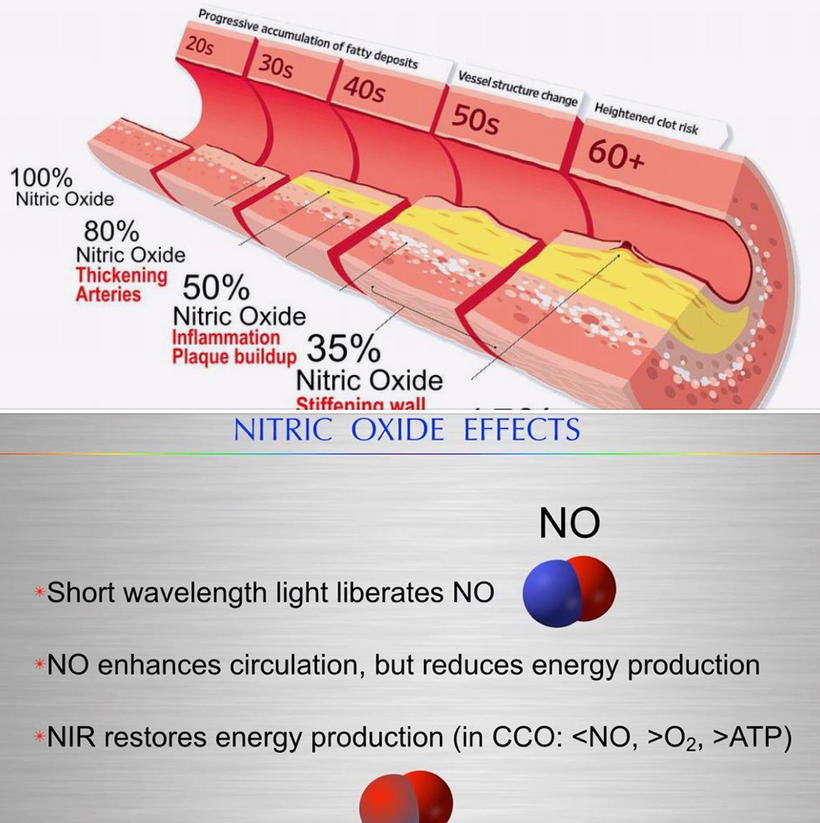

THE RICK RUBIN SIDE BAR: Did you know methylene blue acts by reacting within RBC to form leukomethylene blue, which is a reducing agent of oxidized hemoglobin converting the ferric ion (Fe+++) back to its oxygen carrying ferrous state(Fe++). The dose commonly used at surgery is 1-2mg/kg of 1% Methylene Blue solution. Did you also know that methylene blue can increase NO delivery to tissues as it drops of more oxygen in this maneuver in states where pseudohypoxia or hypoxia exist and NAD+ has dropped? I’ve told a couple of clients that. This advice comes from the story that is unfolding for you in this blog. MB can be used to increase the band gap of broken degenerating photoreceptors inside of sick mammals and silly talking monkeys too.

BACK TO THE STORY

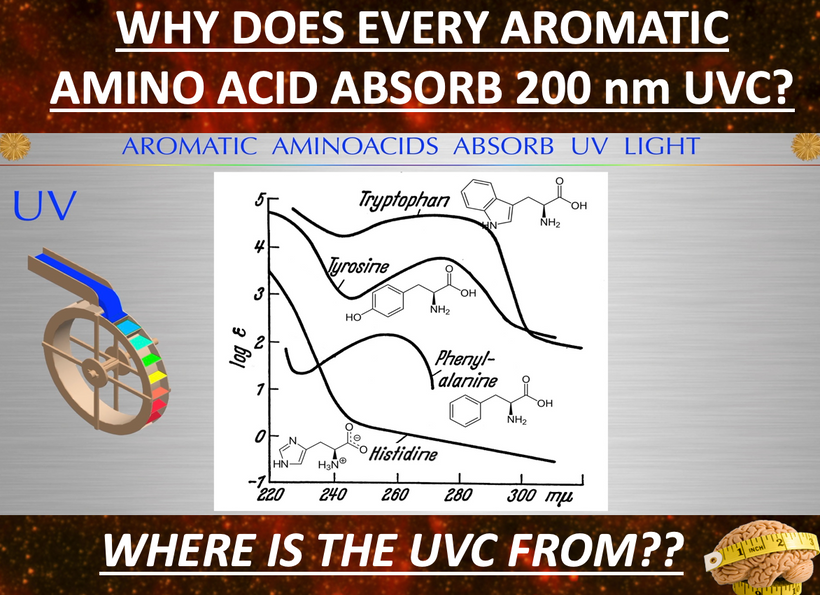

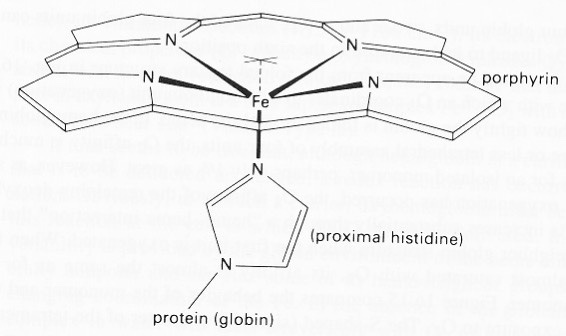

Early versions of hemoglobins suffered from this problem = myoglobin. Later on mammals figured out a novel way to stabilize hemoglobin using UV light when oxygen filled the atmosphere. First I have to explain how we got there. Modern versions of hemoglobin in normal red blood cells are protected by a reduction system in the RBC by an aromatic amino acid (histidine) and by a sea of electrons from the water in blood.

The surface of Earth was getting pounded by UVC light for long periods of time. Since life was totally prokaryotic and anaerobic 2.7 billion years ago when cyanobacteria evolved, it is believed that oxygen acted as a poison and wiped out much of anaerobic life, creating an extinction event of the old guard in life including LUCA. LUCA = last unknown common ancestor.

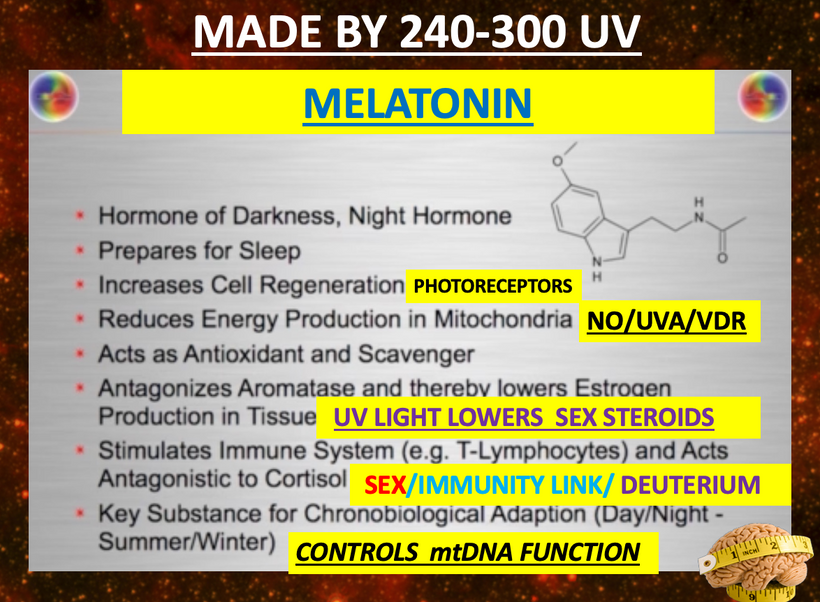

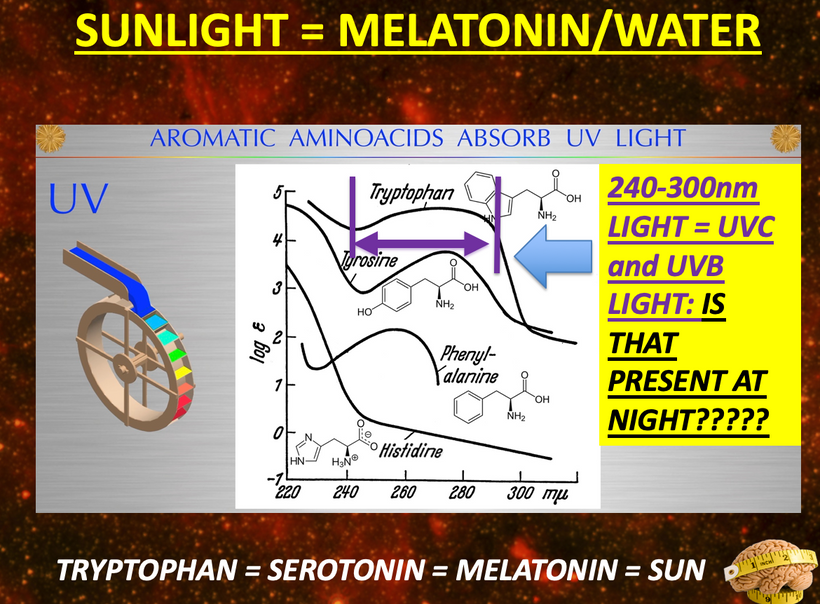

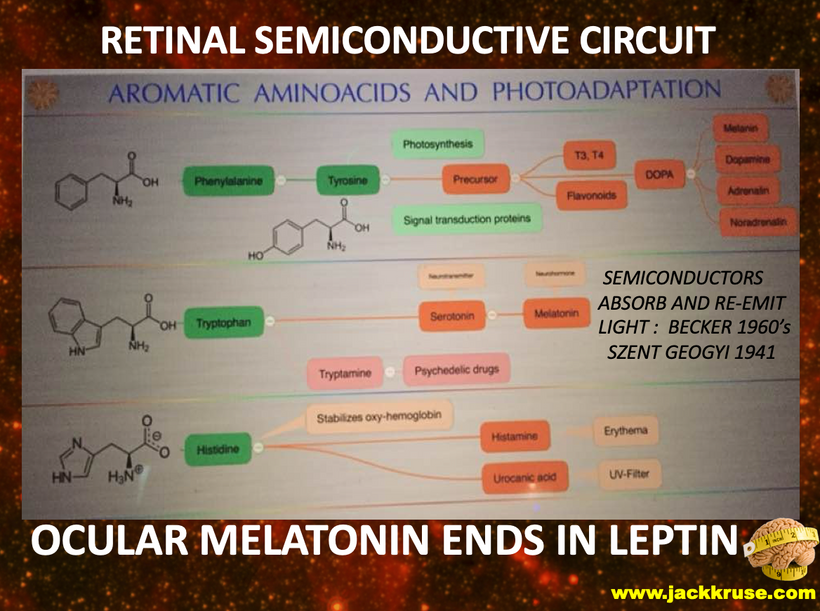

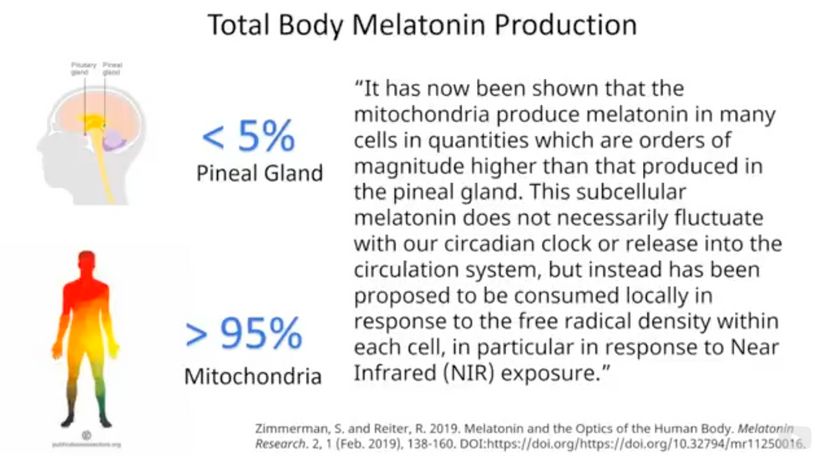

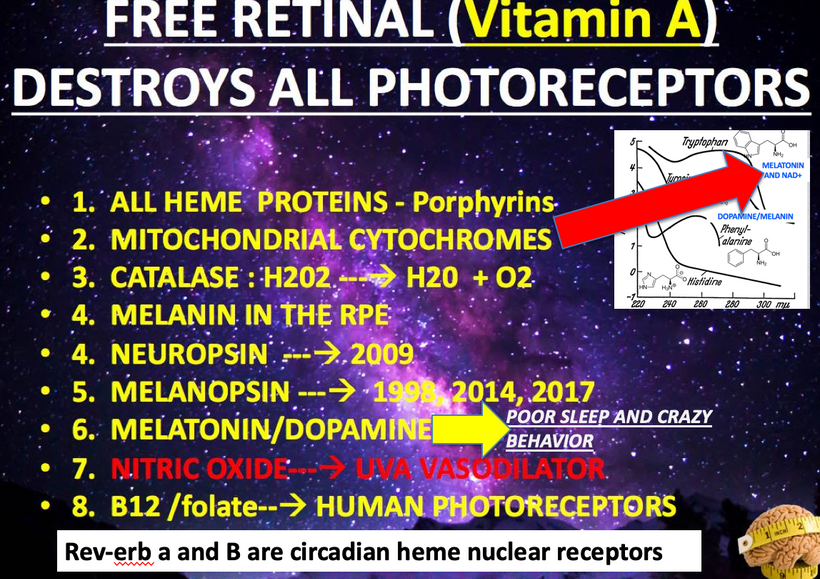

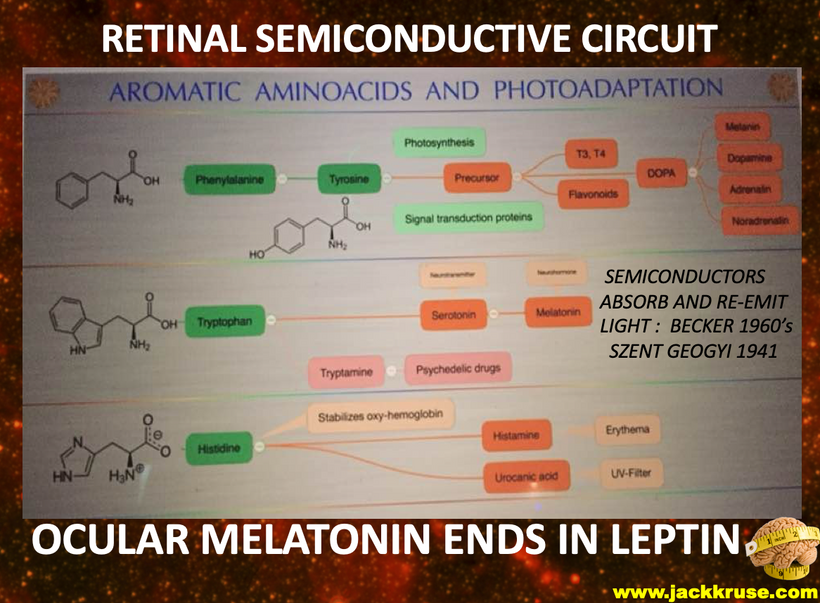

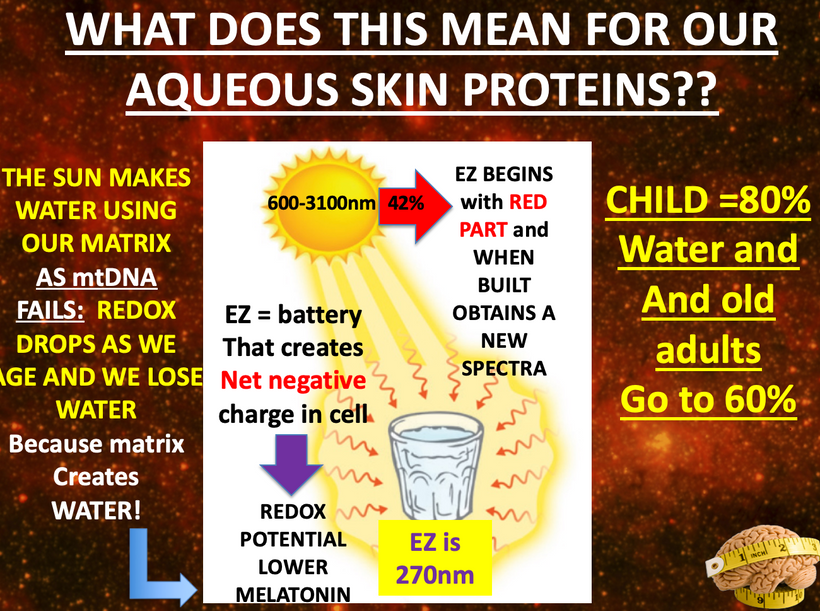

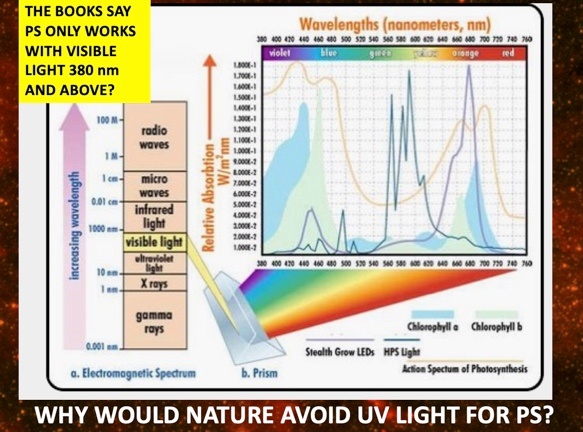

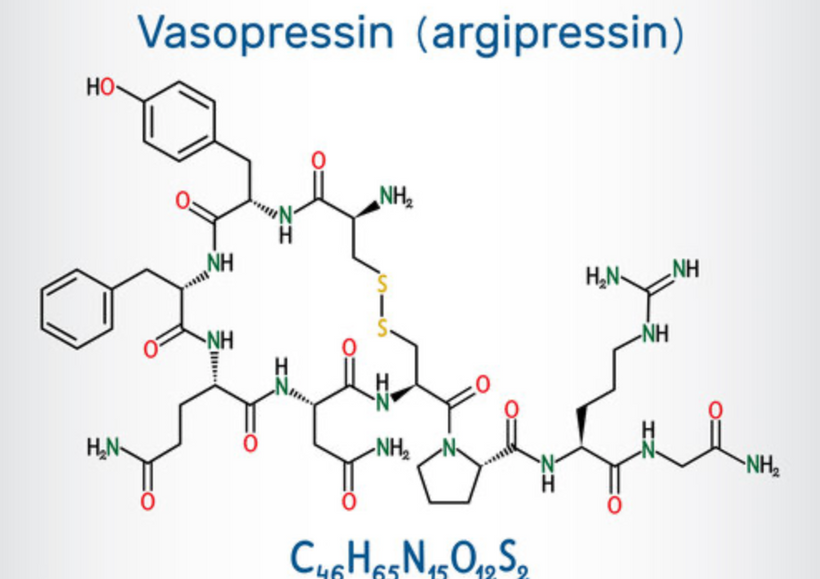

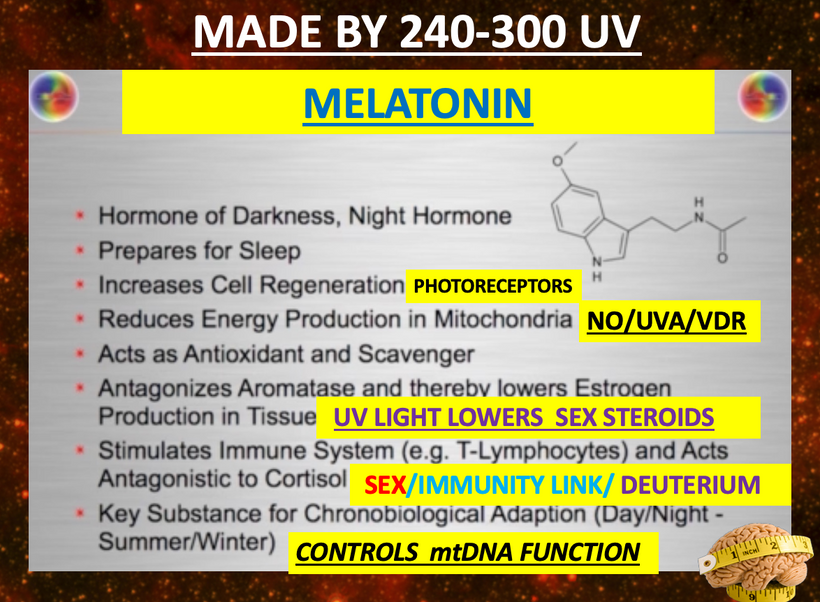

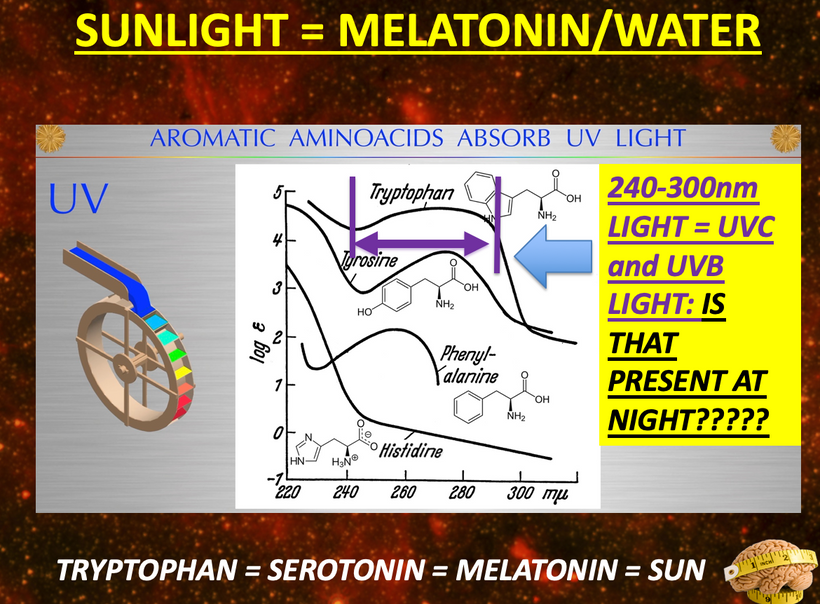

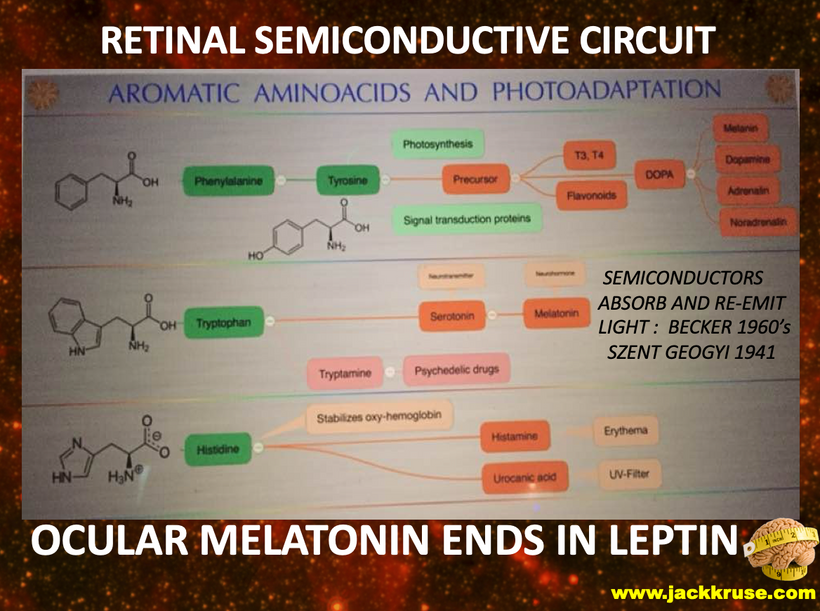

This environmental change drove evolutionary pressures to begin to innovate proteins that used aromatic amino acids to build the most important parts of modern metabolism we see today in cells. Their absorption spectra can go from 150nm VUV to 400 nm UV-A light. Melatonin is one of the most ancient semiconductors known. Its functions have evolved as the Earth changed.

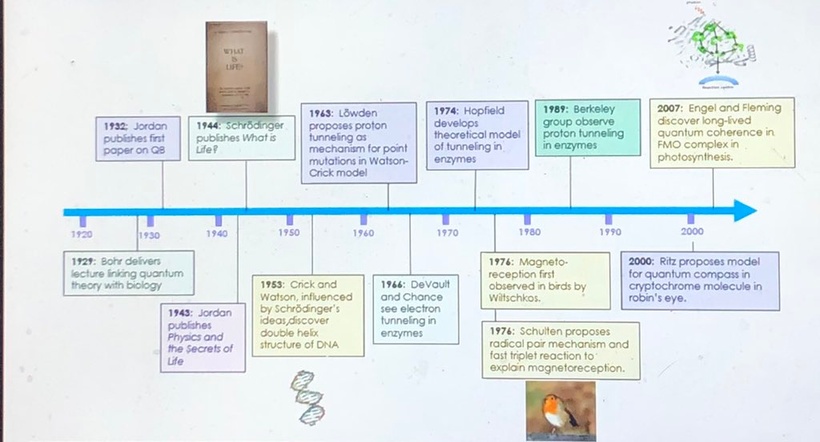

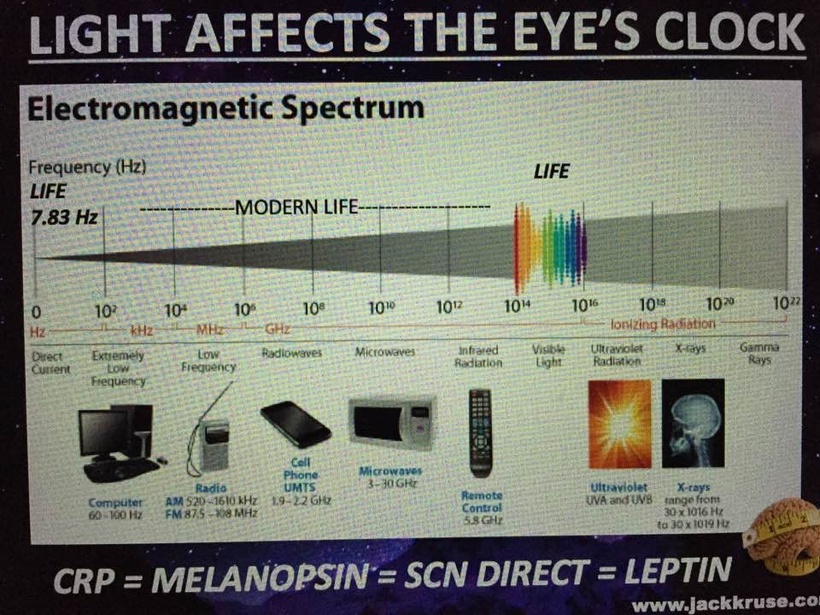

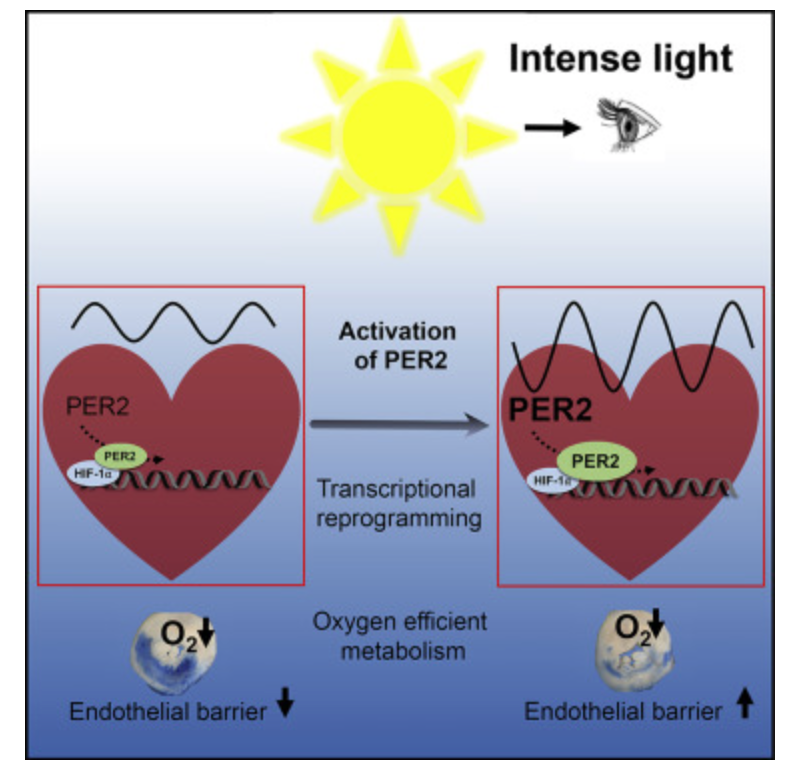

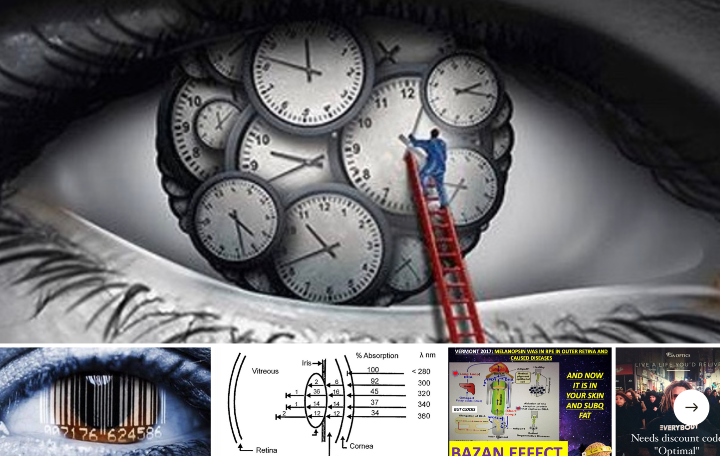

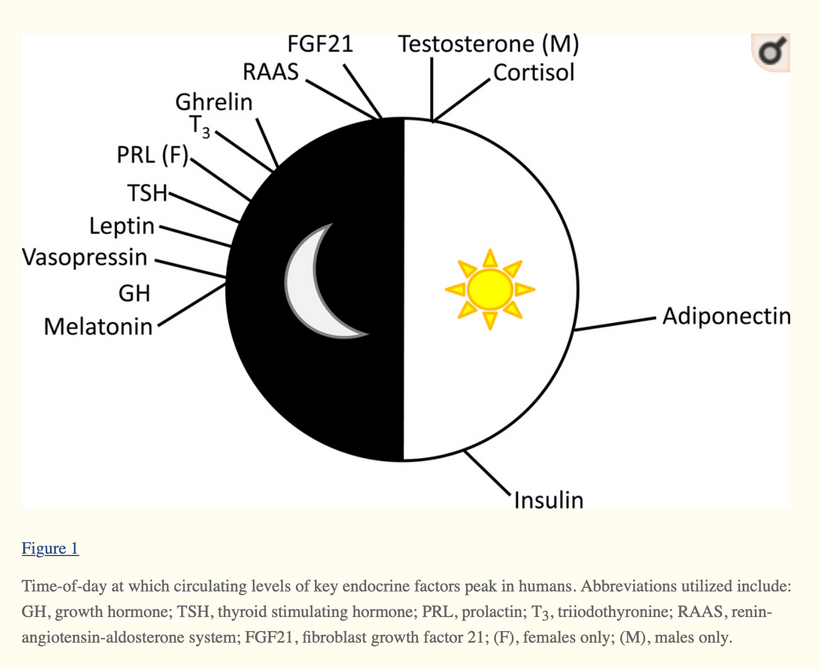

Melatonin, NAD+/NADH, dopamine, adrenaline, leptin, epinephrine and many others. Light controls the flux of all these biomolecules because of movements of H+ in cells. Remember all enzymes that create these chemicals use proton tunneling to get the job done. Proton tunneling is linked to HIF-1alpha and PER2 gene that uses light to increase the periodicity of molecular clocks in cells.

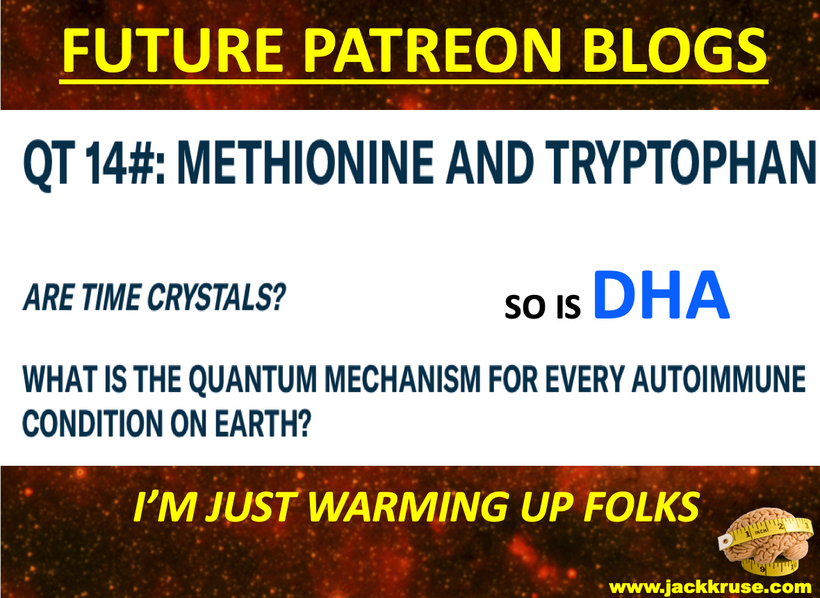

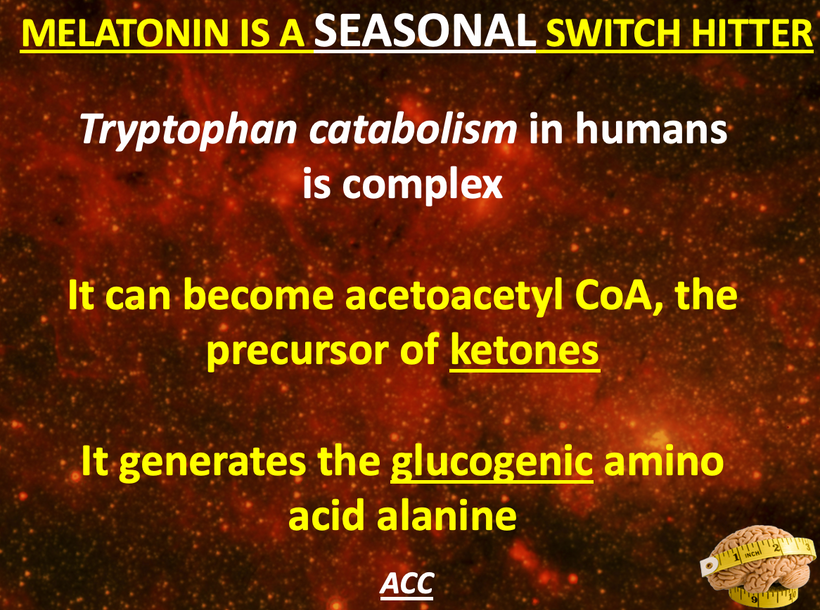

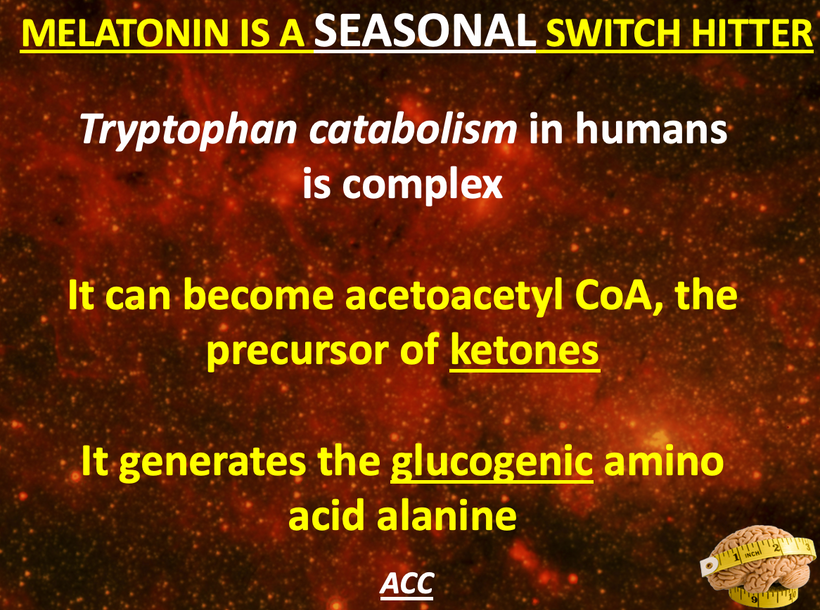

Tryptophan, another aromatic amino acid, became very useful as a time crystal for cells because has only one DNA codon and it catabolism changes as light changes with the tilt of Earth that gave us season. NAD+ and melatonin are made from tryptophan. I wrote those blogs years ago and gave them to you here.

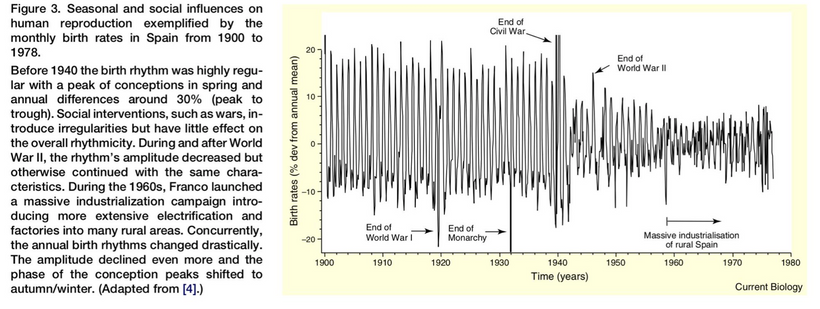

Future life forms would need this information because oxygen gave us cool seasons and hot seasons all in one year as the Earth revolved. This cyclic pattern was built into cell metabolism as it got more complex as the slides below show.

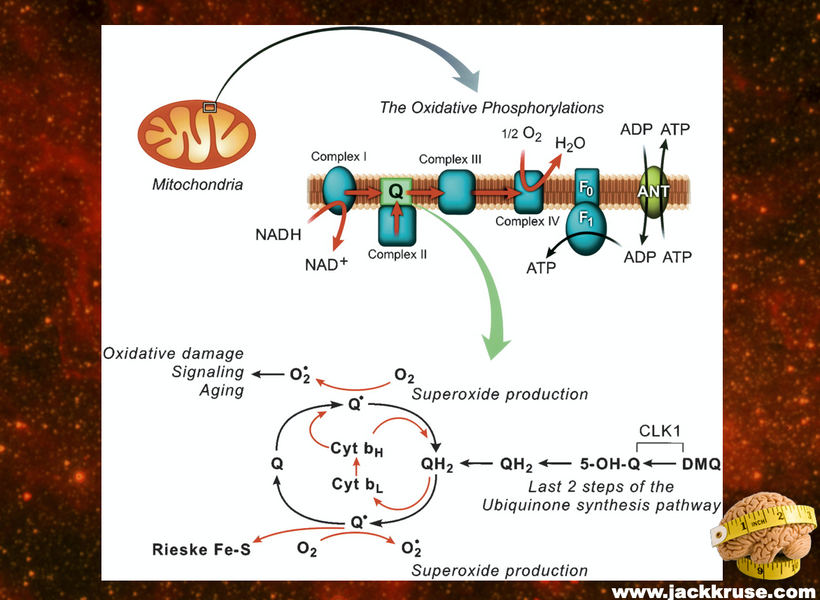

Since oxygen has a high redox potential, it acted as an ideal terminal electron acceptor to generate energy after nutrient breakdown. Oxygen soon became indispensable for metabolic activities. Organisms also evolved strategies to detoxify the reactive oxidative species that resulted from aerobic metabolism.

Though sequencing and phylogenetic analyses estimate the evolution of ROS detoxifying enzymes even before the advent of aerobic microbes, the Great Oxidation Event acted as the catalyst to shape the directed evolution of enzymes like superoxide dismutase (below) and catalase. Catalase (below) is one of the earliest heme proteins along with ancient myoglobin and hemoglobins.

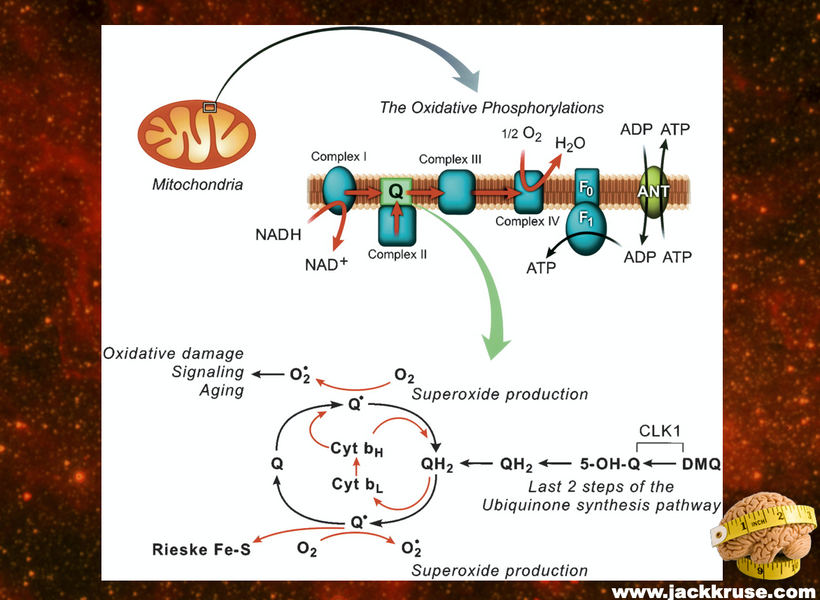

Note the presence of wide band semiconductor components in the picture above: the Fe-S dopant semiconductors and the roles in creating the free radical signal in mitochondria. Below note how all the chromophore proteins in mammals are linked to aromatic amino acids, heme proteins and melanin at some level. Can you guess why yet?

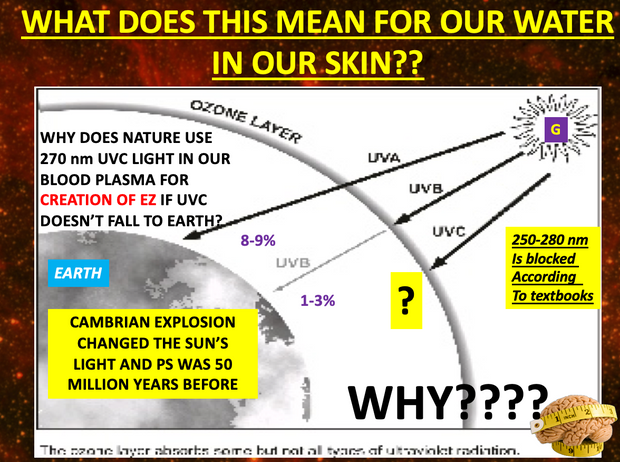

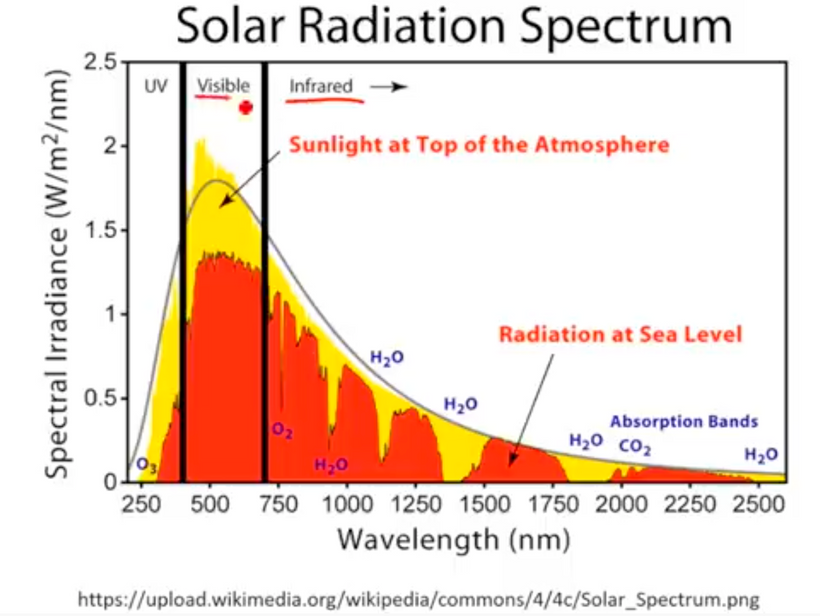

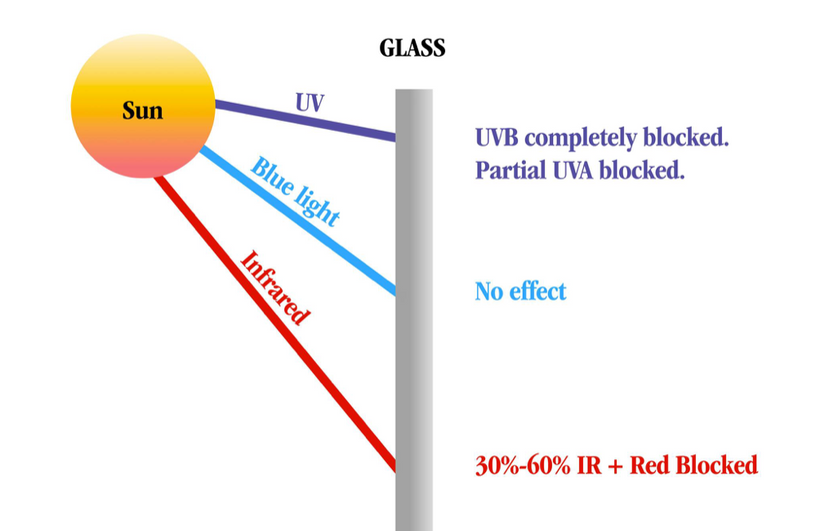

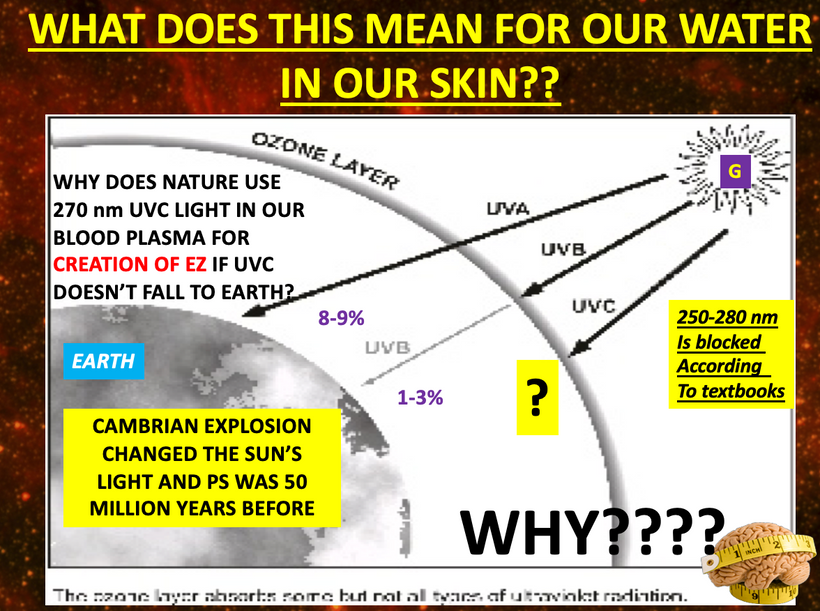

As oxygen continued to mushroom the high ionosphere became filled with a new gas that decreased the terrestrial solar spectrum. Life had to react to this and it fueled changes in heme proteins showing up on the surface of Earth in early life forms.

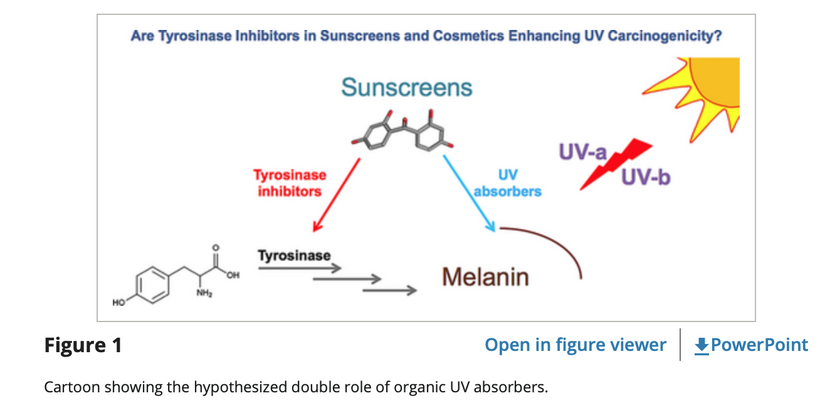

Oxygen was also responsible for formation of the ozone layer in the atmosphere. The UV radiation from the sun split oxygen molecules (O2) into 2 atoms of oxygen, which then reacted with another oxygen molecule to generate ozone (O3). Ozone acts as a natural sunscreen for Earth to prevent harmful UVC and parts of the UV-B radiation from reaching the earth’s surface. This reduction began the the evolution of new semiconductors in the two DOMAINS of life on the surface of the earth below called melanin.

As oxygen continued going higher it fueled the Cambrian explosion and life was able to take advantage of the mirror image of the photosynthetic arm of life on Earth. Namely mitochondria developed. Complex life captured mitochondria in their tissues as a stowaway to transform solar energy into CO2 and water. It transferred electrons from food to oxygen to fuel this solar battery. At this point in time, life exploded and all complex life on Earth we know about today showed up almost over night. Eukaryotes came from the fusion of the other two Domains in a process called endosymbiosis. We believe chlorophyll and mitochondria innovated at this time.

MELANINS CONTINUED TO EVOLVE IN MAMMALS ON THEIR SURFACES BUT ALSO INSIDE OF THEIR TISSUES:

THE KT EVENT

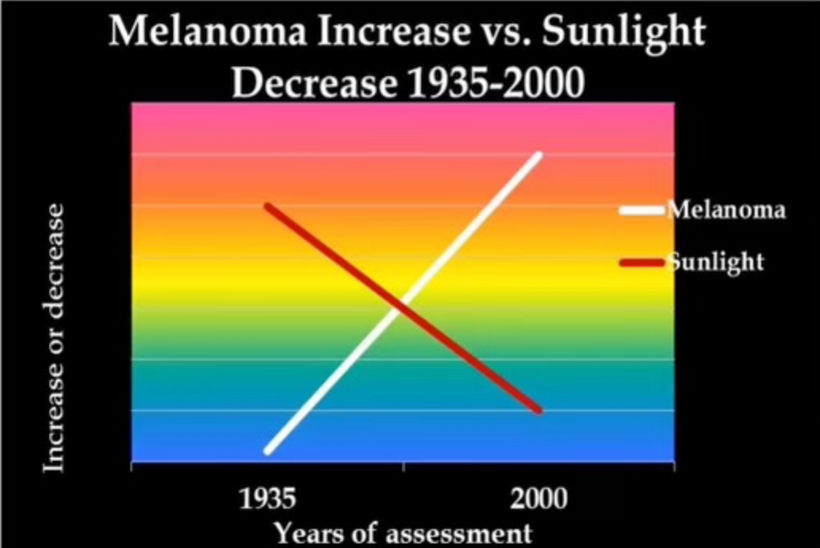

Melanin was a new type of wide band gap semiconductor. It was innovated because it was able to absorb all frequencies of UV light. Mammals began to dope melanin by putting atoms next to melanin that high band gaps to make UV light within their own tissues. Mammals took their surface melanin in their hair and internalized it to make sunlight because the asteroid dimmed sunlight! The dimmed sun was the epigenetic signal they used to do this.

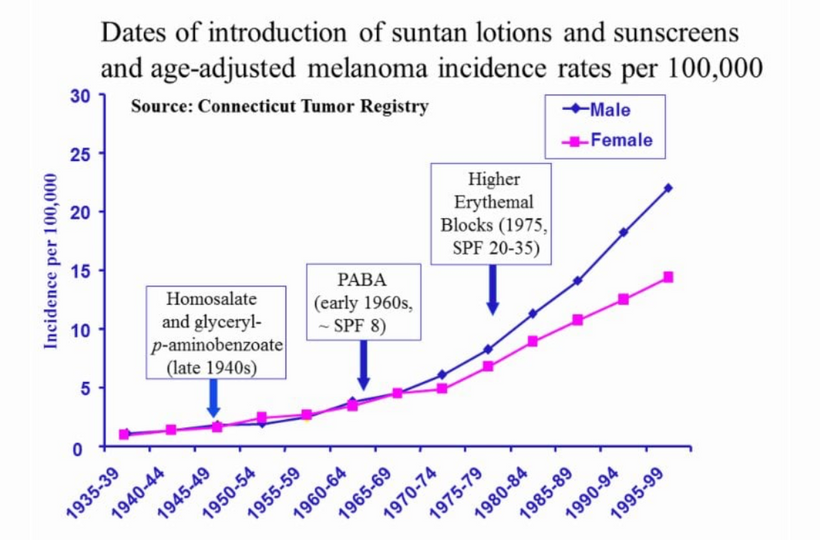

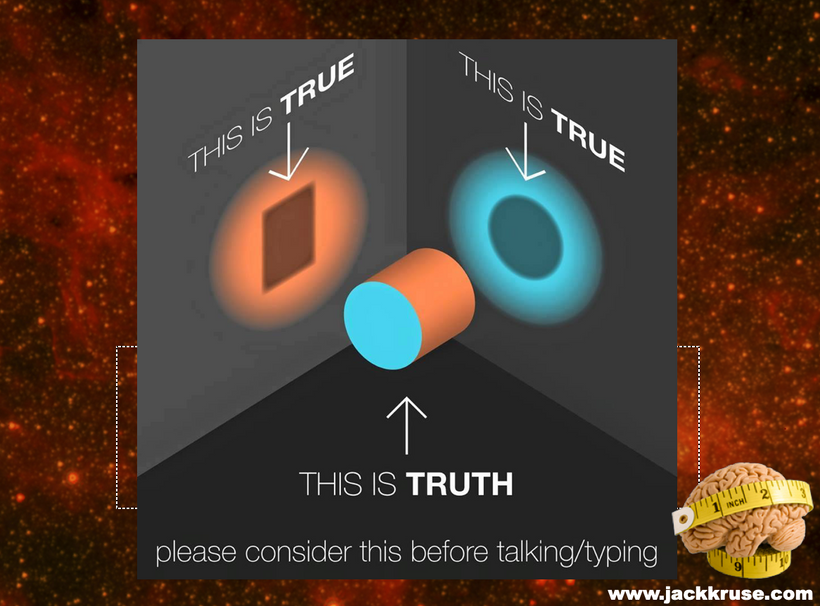

Modern centralized researchers/science have the story backward on melanin. They believe melanin’s job in nature, at least in our skin, is to convert light energy very rapidly to heat, which water absorbs, and this is the safest way to dissipate it before radicals can be generated.

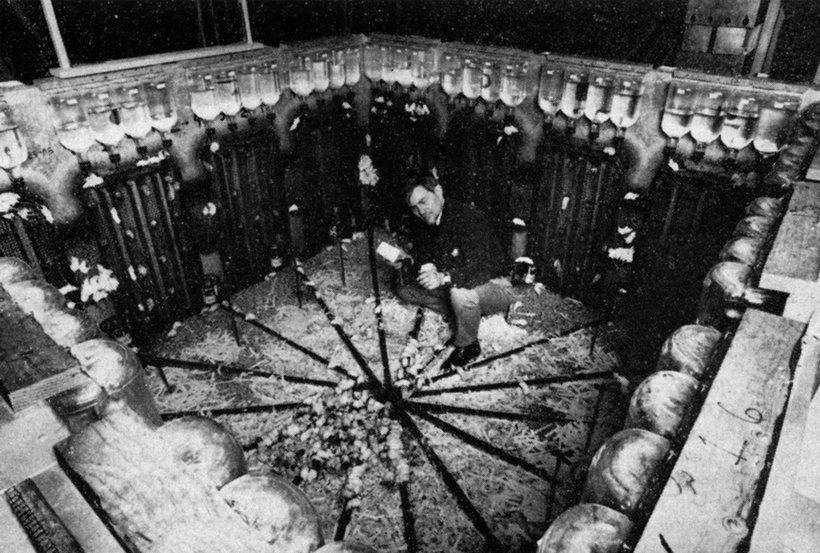

Melanin is plentiful in mammals internally, not just on their skin. The centralized science version of events makes no sense in this case. Their focus is on the skin only and meloma prevention. Their ideas are pictured on the black walls below. My idea is in the foreground below.

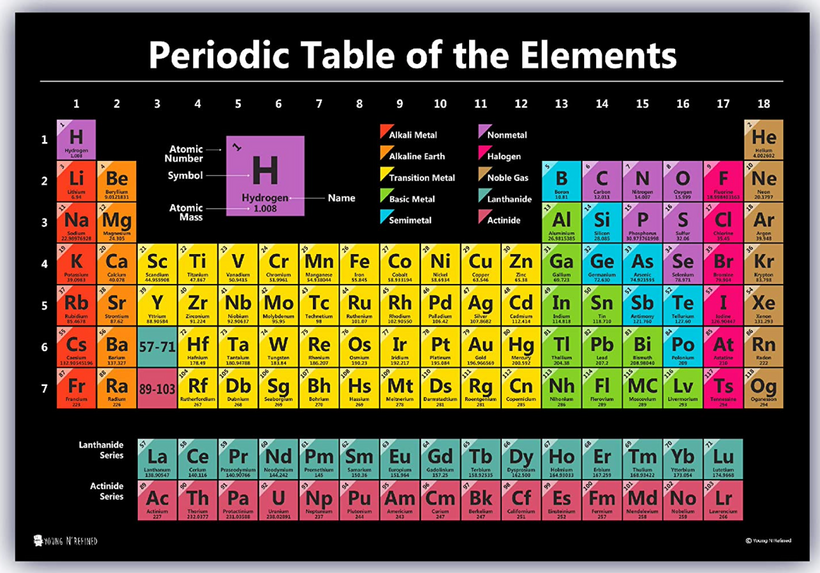

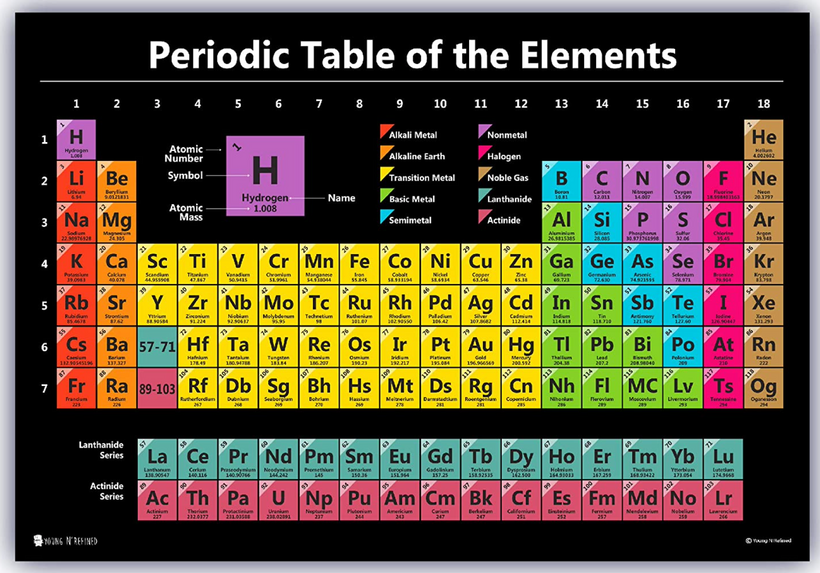

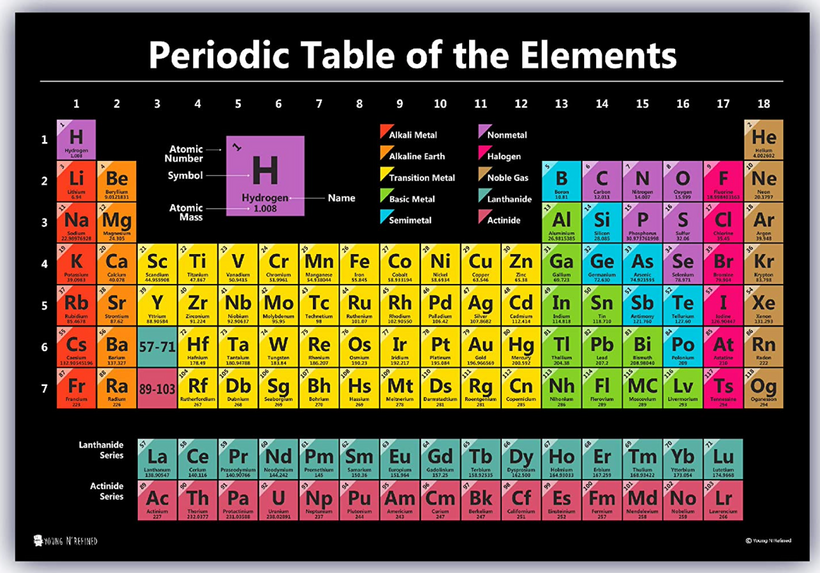

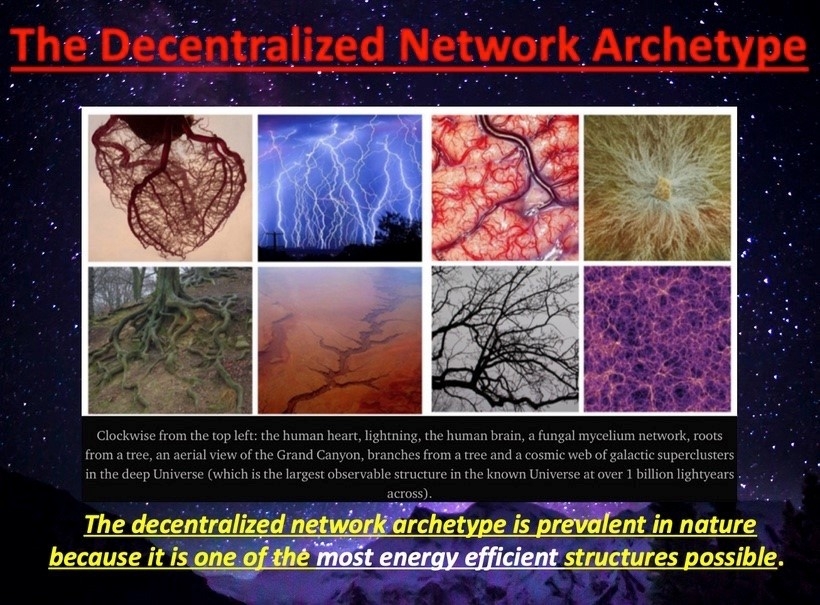

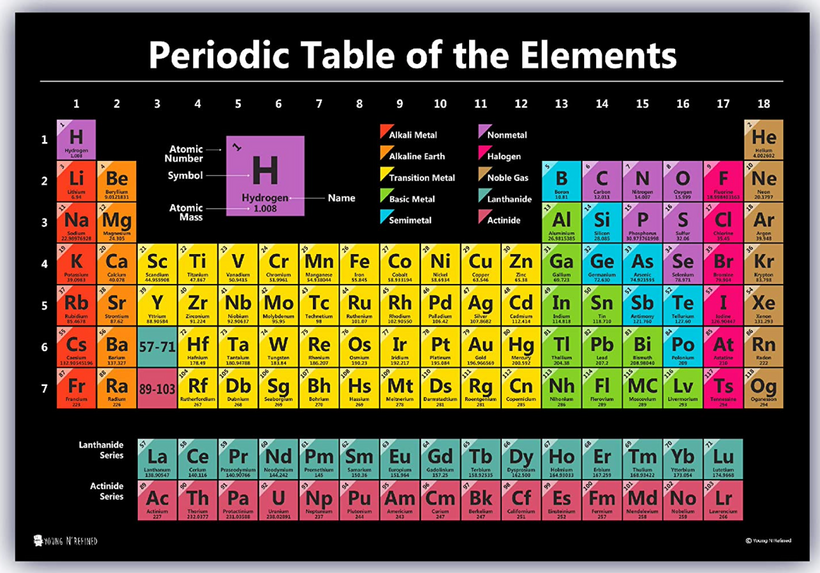

The decentralized mind sees the same data and realizes that internal melanin of mammals has to have some unique atoms next to it to create energy missing from the sun. Since melanin is dark it absorbs all types of light around it This is what band gap theory of color tells us. It seems centralized biologists do not read physics journals. This color makes melanin the ideal biological solar panel. It is not sunscreen; it is an internal panel cells use to regenerate mammalian tissues using Group 2,3, and 4 atoms on the periodic table as their partner in crime. This explains why cells like Na, K, Ca,Mg, Fe, S,Cl, and P. It also explains why 56 enzymes in mitochondria use Mg at some level and why the P in ATP is one of those atoms.

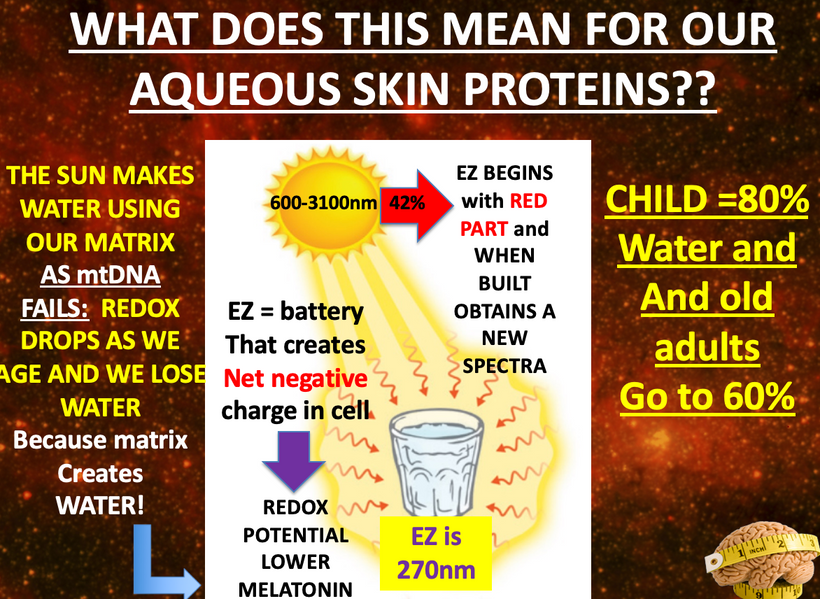

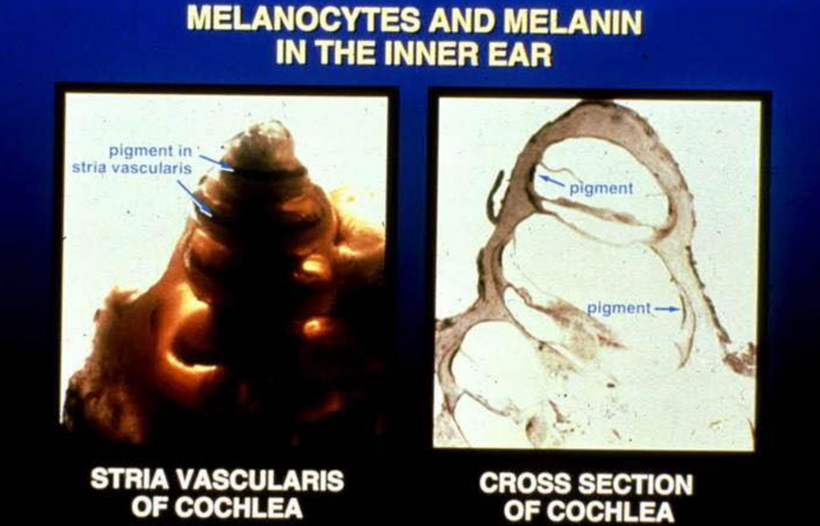

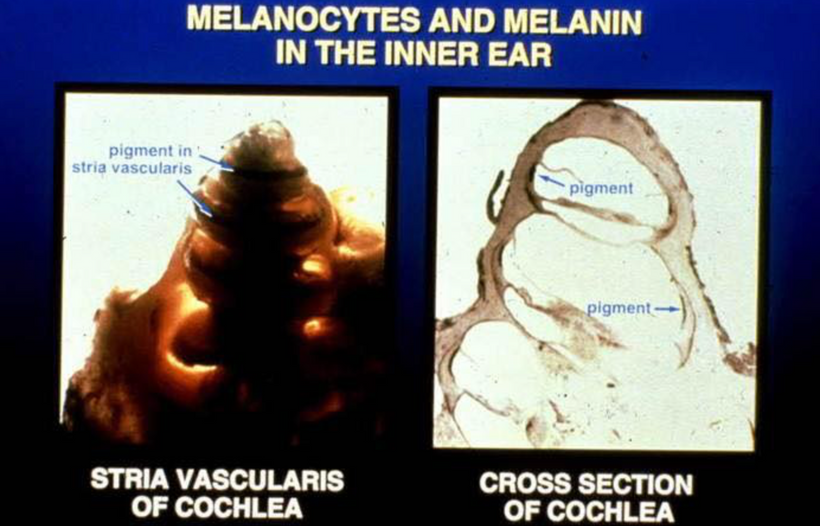

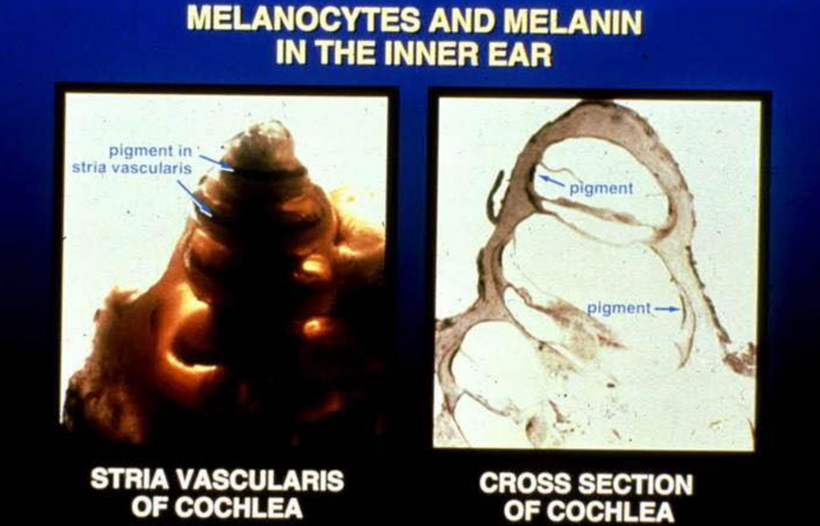

For example in the ear, mammals have evolved their endolyphmatic sac to have a fluid in it with high levels of potassium adjacent to the melanin. The DC electric power (pic below) generated by mitochondria interacts with aqueous KCL in our cochlea large amounts of UV light is made. Melanin absorbs all this light. This occurs because KCL has a band gap of that spans ALL UV frequencies that go to 150nm-400nm light. Now we see why cells in mammals favor aromatic amino acids wherever semiconductive proteins are found because their absorption spectra can handle them without any free radicals creation to be transferred to surrounding water.

Potassium is the diode in this semiconductor and the DC electric power in the cell from the mitochondria causes it to create 150-400nm UV light. Melanin absorbs it all IN TOTAL. Nothing goes to waste. Nothing creates free radicals. Melanin is able to shares the energy transformed with adjacent chromophore proteins who have different action spectra. Melanin also uses quantum effects that have escaped biologists. Proton tunneling not only is used in enzymes but it is used in melanin. It undergoes a reaction called a partial proton transfer with water molecules to render deep UV light safe inside our bodies. Remember all of a cells semiconductor are hydrated.

Now you know the reason why they are. This stops the extreme ultraweak UV light from prompting free radicals to harm adjacent molecules to cause tissue damage. Every living cells creates ELF-UV as Fritz Popp showed in his photomultiplier experiments over 50 ears ago. Melanin replaced missing sunlight in mammals post KT event so they could survive and eventually thrive!

These environmental pressure are what gave rise to the warm blooded small creatures who could handle these temperature shifts from rising oxygen tensions as the Earth revolved around the sun. I spoke about these shifts that early complex life had to deal with in my Cold Thermogensis series of blog over 15 years ago. These combined environmental stressors drove mammals do begin to change their interiors bu using melanin in the furry coats to do it.Remember mammals all have to have hair to be a mammal. This is where ancient mammals buried their melanin. But this is why they remained small and underground.

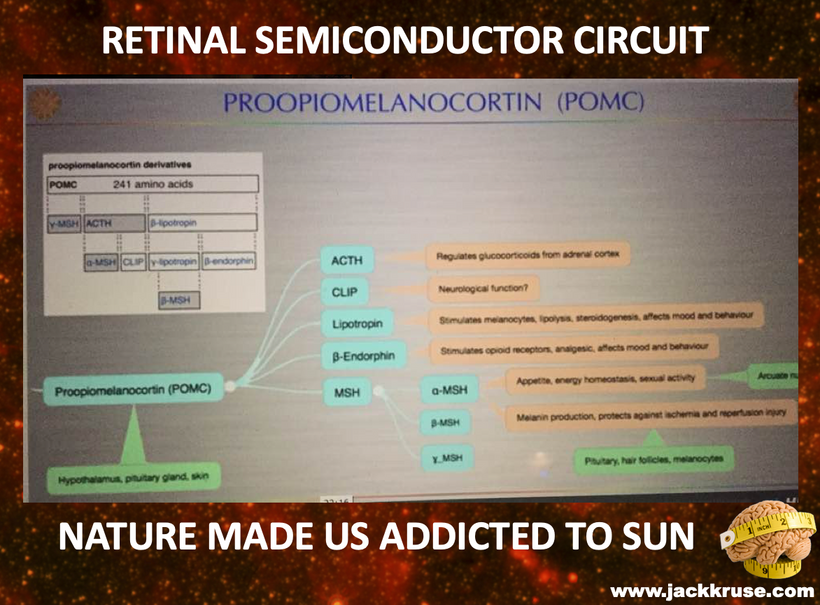

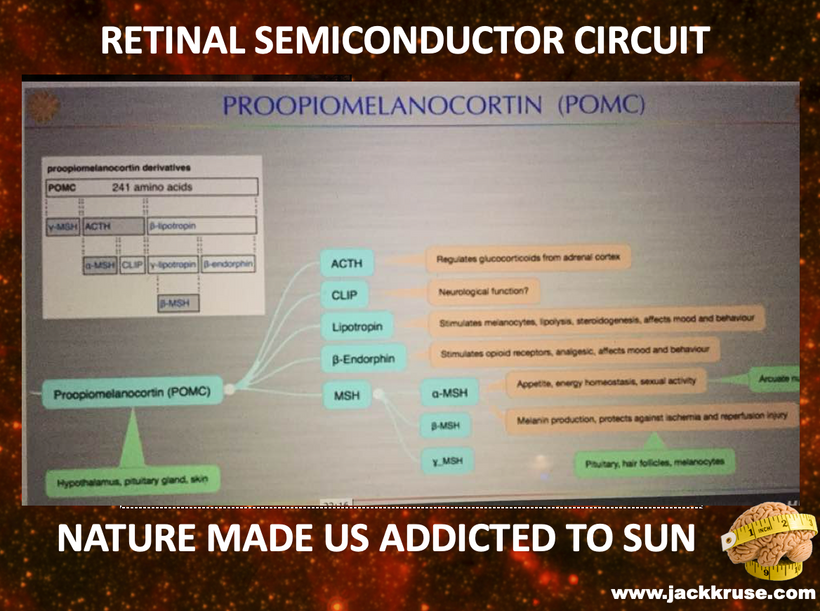

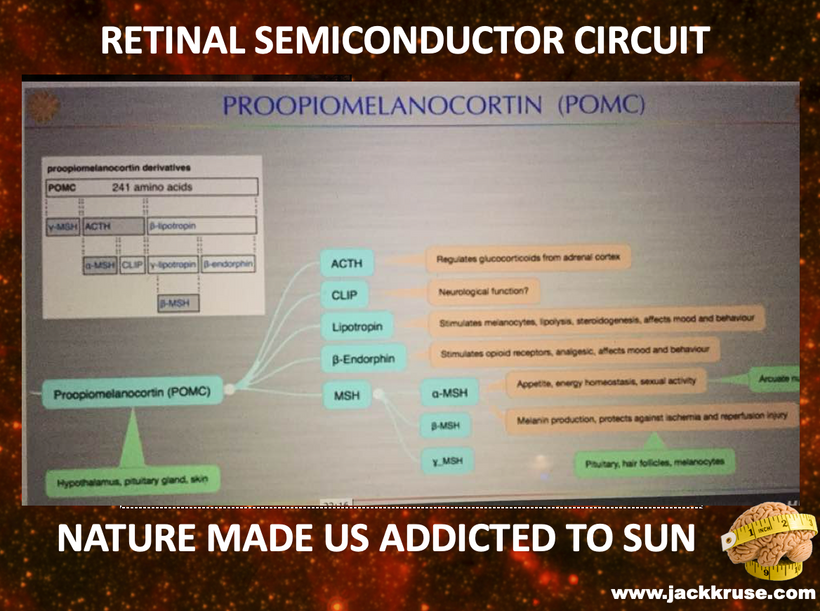

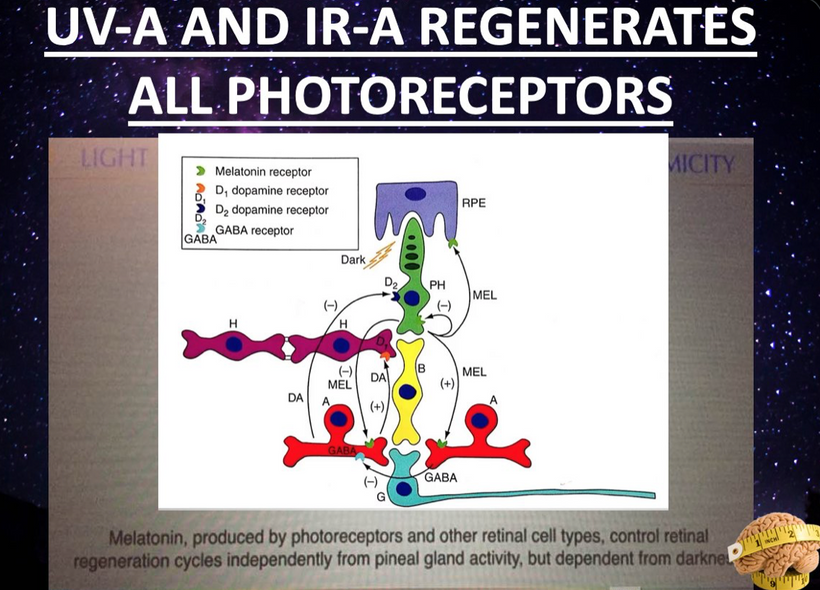

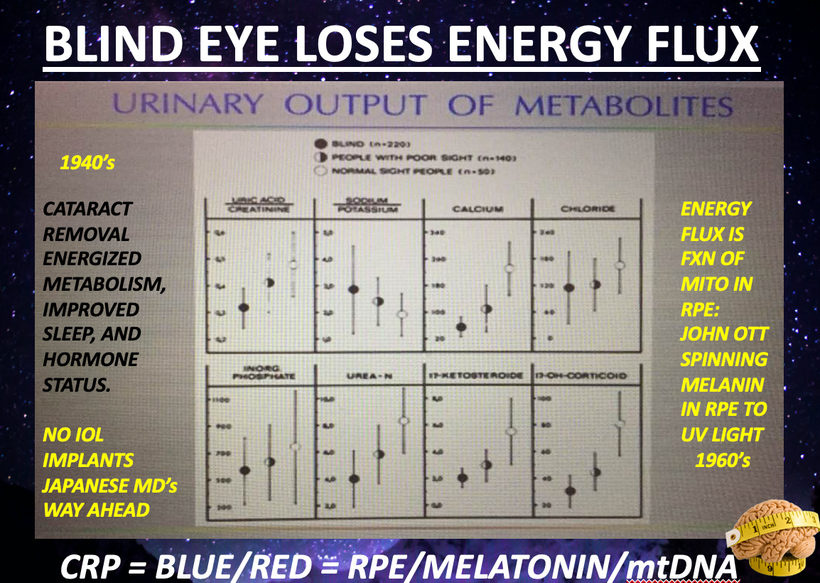

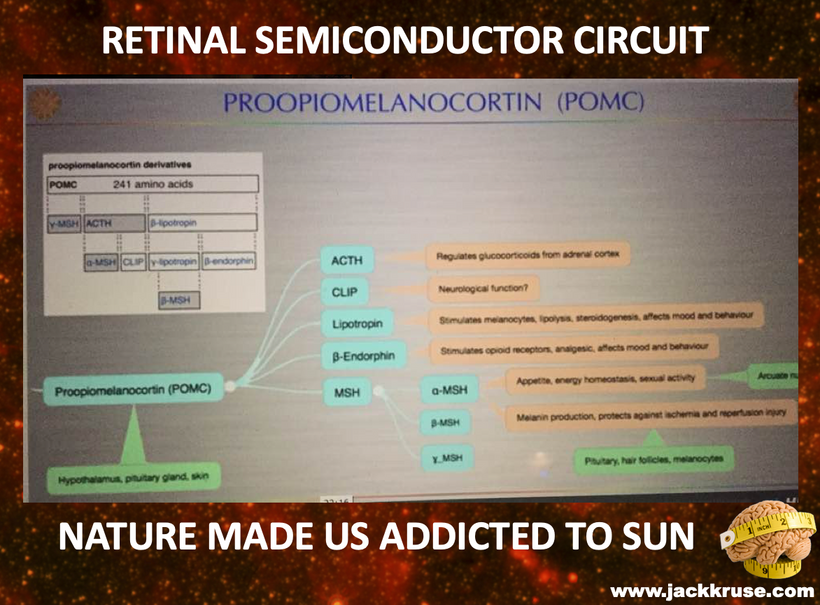

One of the first ways mammals evolved post KT was putting melanin in the eye in the RPE. They did this with POMC as well, to form the leptin-melanocortin pathway in their eyes and brains. <——CT 6 was born. This is a semiconductive circuit in the eye of all mammals. You’ll note below that histidine a UV absorbing protein stabilizes hemoglobin chains to deliver oxygen to mitochondria as I mentioned above.

Life got used to oxygen being plentiful for the last 2.5 billion years until something stopped the oxygen party on Earth An extraterrestrial event interrupted sunlight and stopped photosynthesis for a period of time. We do not know how long it went on but we do know it ended the age of dinosaurs and began the age of mammals. This drove melanin from their furry surfaces to their interiors. It also fueled the innovation of HIF 1-alpha and linked it directly to the PER 1/PER2/PER3 gene of the circadian mechanism.

This KT event drove further evolutionary trajectory in the mammalian clade because it acutely made both UV light and oxygen scarce for a period of time. That drive semiconductor innovation at the quantum level. The interruption of photosynthesis made oxygen quite valuable to the semiconductor-fabricating plants in cells on Earth in cells. The other two proteins that were altered as melanin was driven inside of tissues were chlorophyll and hemoglobin.

The reaction that turns molecular oxygen (O2) into water releases lots of energy, and all animals need that energy to drive their body’s functioning. The half-reaction and associated free energy change are:

O2 + 4H3O+ + 4e- –> 6H2O delta G = -305 kJ/mol

This is a massive amount of energy. This energy was the boost that powered the mammalian clade to take over the world of biology after the last extinction event. There has to be a biological mechanism for capturing oxygen as O2 (in its high-energy, zero oxidation state) and bringing it to a place where it can be turned into H2O (this is a reduction reaction) in such a way that the energy released by this process can be profitably used by the organism.

This is accomplished in most organisms via hemoglobin and/or myoglobin, which are often referred to as oxygen-carrier proteins. An iron atom in the center of myoglobin binds to O2 and takes to where the energy is needed. Hemoglobin works almost exactly the same way except that where myoglobin has only one iron-containing protein subunit, hemoglobin has four. When one of hemoglobin’s four irons binds an O2 molecule, the other three protein subunits’ iron atoms can bind O2 more easily. This is called the “cooperativity effect”

Every time I post this slide above I wonder what my readers really see. Then I wonder what they understand about these two molecules. What they mean to you is not what they mean to me. Why?

They are nitride-based semiconductors ideal for creating blue and green light-emitting devices found in biological systems favored by evolution BEFORE the KT event.

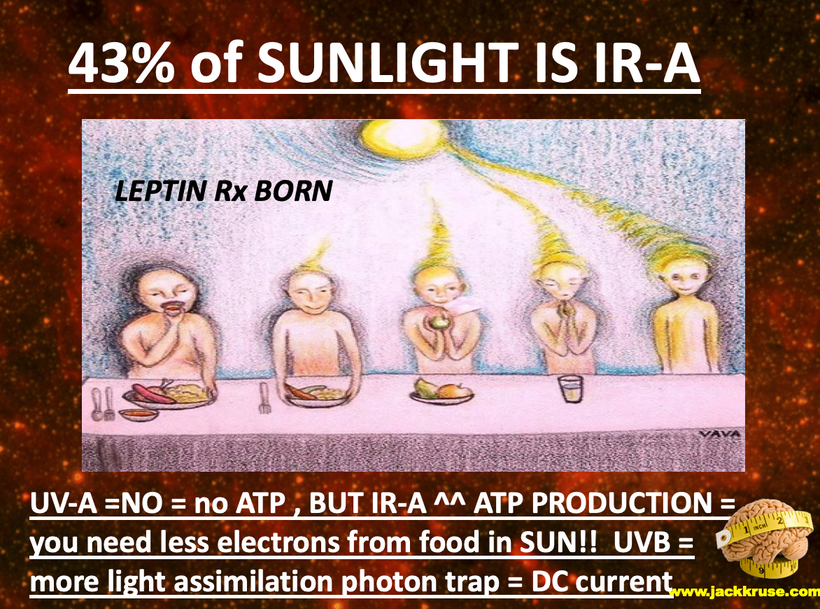

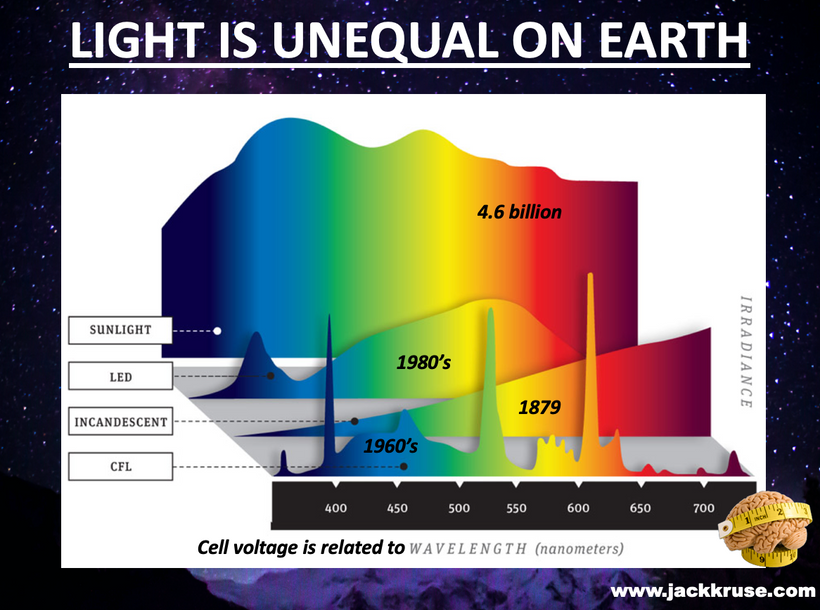

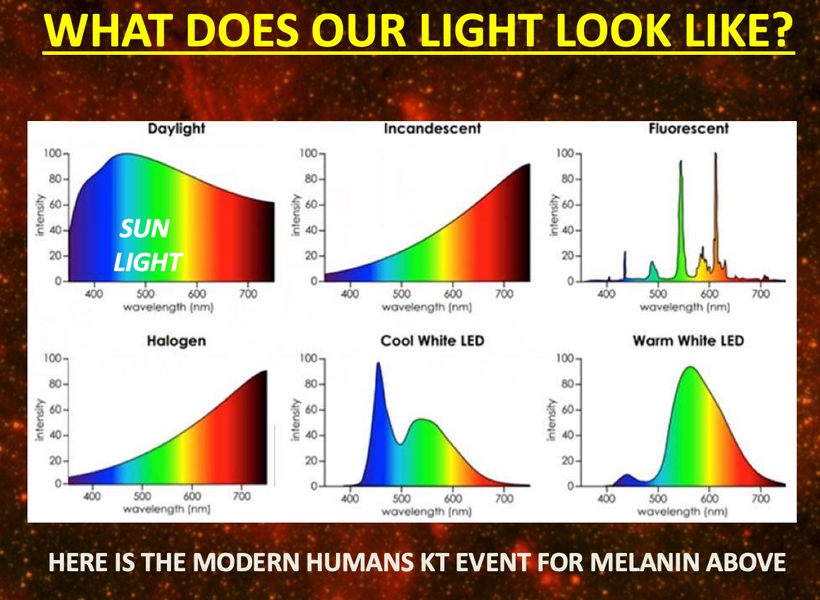

The KT event happened 500 million years after the Cambrian explosion so it is an ancient semiconductor that evolved because of the oxygen event on Earth tied to photosynthesis changes in the sea by DHA of algae. Melanin is a unique dark pigment-wide-based semiconductive protein favored by evolution AFTER the KT event. Below is the new KT event for modern humans in two pictures.

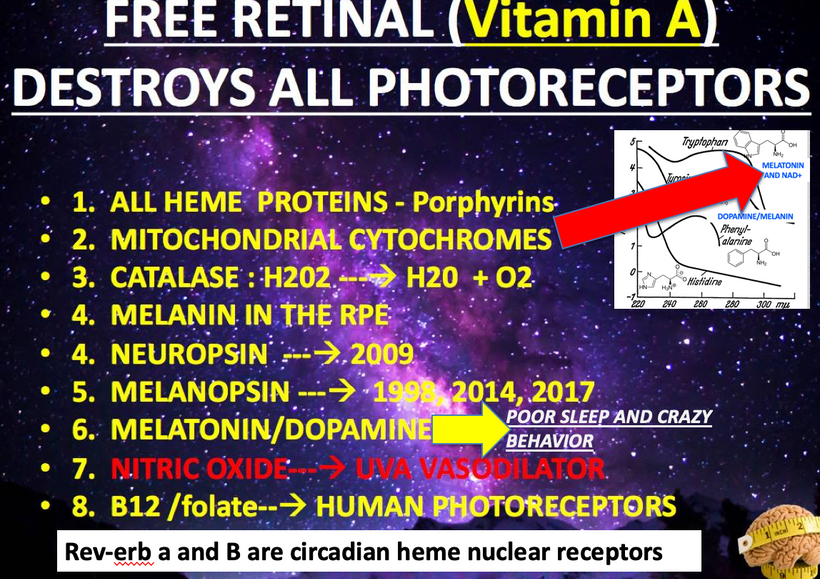

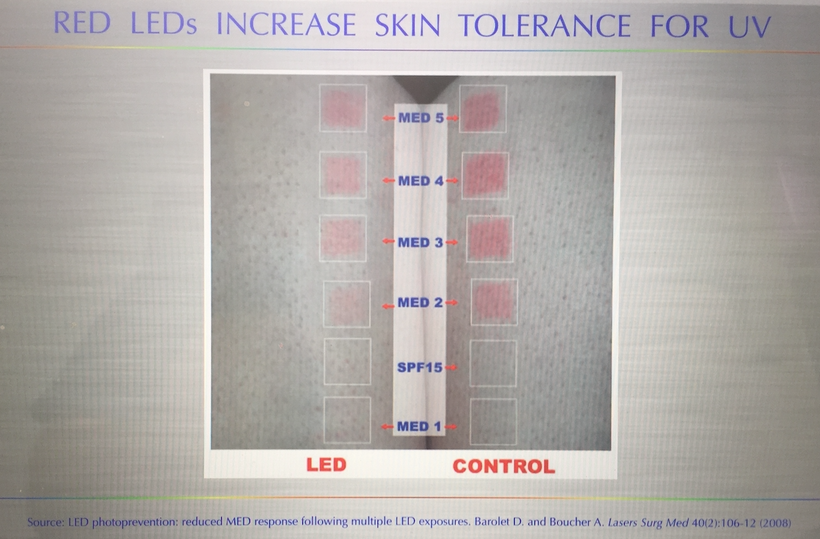

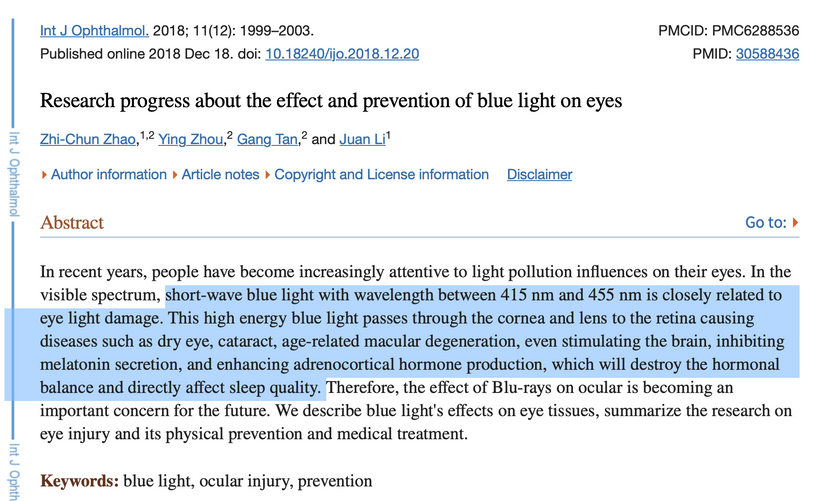

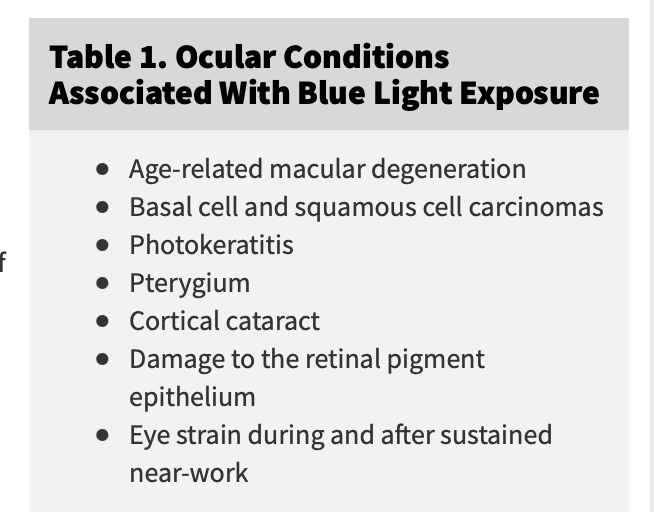

This light above in 5 of the panels destroys all wide based semiconductive proteins in mammals exteriors and interiors. The picture below is how we destroy the ones on our surfaces. Sunglasses, glasses, intraocular lens, and contacts being the other.

Why was hemoglobin favored BEFORE the Cambrian explosion?

(1) hemoglobin as molecular heat transducer through its oxygenation-deoxygenation cycle

(2) hemoglobin as a modulator of erythrocyte metabolism (ferroptosis)

(3) hemoglobin oxidation as an onset of erythrocyte senescence

(4) hemoglobin and its implication in genetic resistance to malaria in the human cradle of life in the East African Rift

(5) enzymatic activities of hemoglobin and interactions with drugs to deal with met-Hb. (methylene blue)

(6) hemoglobin is a source of physiological active catabolites to create unique semiconductors.

I wonder if my readers realize that both of these molecules are the semiconductive proteins that became favored by cells 65 million years ago to let life bounce back once the asteroid destroyed the reign of dinosaurs thermodynamically?

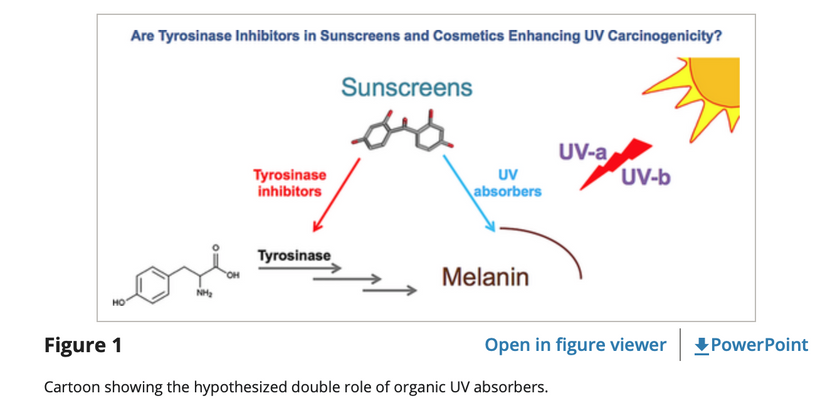

Biophotons sculpted and created future iterations of mammals using oxygen and sunlight as their starting point. Hemoglobin favored the development of the melanin system in the neuroectoderm of mammals to sculpt life after this extraterrestrial event changed the spectrum of sunlight. Melanin allows mammals an advantage to live in low sunlight conditions. This means blocking melanin from its job will destroy melanin-containing tissues and their abilities in the mammalian clade.

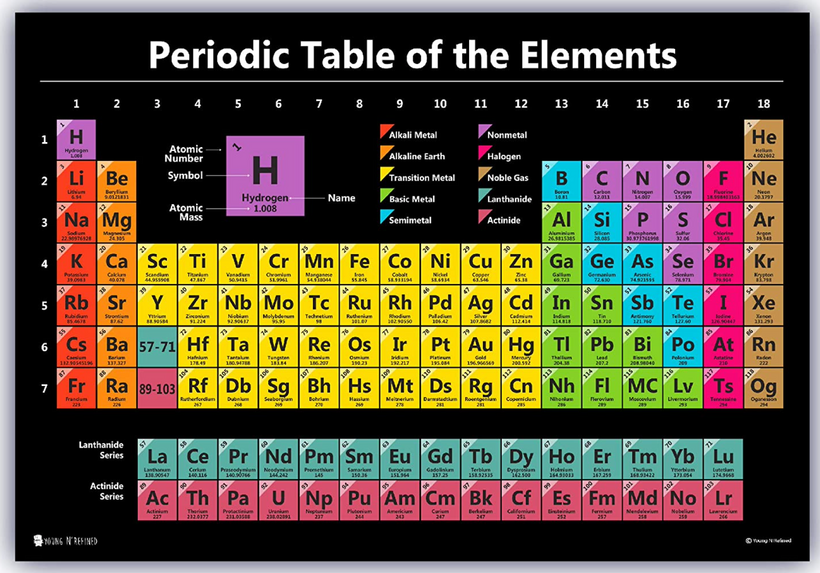

Hemoglobin and chlorophyll are wide-band semiconductors. Wideband semiconductors are found in Groups 2, 3, and 4 on the periodic table of elements. Nitrogen and Iron are also in those periods. So is sodium and potassium.

Another example of a wide-band semiconductive device that was favored after the KT event is found in the human cochlea Imentioned early. Now I want you to get the full picture. The cochlea is a spiraled covered internally with a wide-based semiconductor sitting in endolymph fluid. A remarkable characteristic of the cochlea is the unique composition of endolymph. It is only remarkable to a centralized mind.

The decentralized thinker knows immediately why Nature did this. Potassium is the smallest element in period 4 of the periodic table and it has the ability to build semiconductors that emit powerful UV light that melanin absorbs tremendously. Melanin is designed by nature to replace the sunlight that was missing from the KT event in mammals. This liquid fills the scala media, and is very rich in potassium (150mM), very poor in sodium (1mM) and almost completely lacking in calcium (20-30 µM).

Its spiral shape is lined with a wide-based band gap semiconductor called melanin seen below. Most centralized physicians never learned that melanin was in the ear and this is why they have no idea what causes tinnitus. I do. The fluid in the spiral is loaded with potassium chloride crystal in an aqueous format and it has an energy band gap of 7.6eV.

What does this number imply to decentralized clinicians? The way we hear in our ears is semiconductor based process and it uses UV light to work. Due to the quantum confinement effect, electrons and holes in the semiconductors at the nanoscale level are confined by this arrangement of atoms in the cochlea. Therefore, the energy difference between the filled states and the empty states of potassium increases or widens the band gap of the semiconductor to make it easier to turn sound waves into electromagnetic signals in the cochlea. In the human ear, the melanin absorbs the UV light & visible light into the IR spectra transformed from its potassium diode (E=mc^2) and passes this light energy to the water in the endolymph and in neurons of the eight cranial nerve. Any light not captured by melanin is picked up by water. All neurons release water when they fire an action potential, FYI.

Potassium chloride emits VUV-IR light in the endolymph, and forms excited electronic states in melanin that decay on ultrafast timescales that are topographically organized to excite other semiconductors in the organ of Corti that allow you to hear.

Melanin as a pigment has now been identified to have other functions apart from being just a bio-macromolecule. It is found to be among the most unique organic semiconductors on Earth. Melanin tends to be amplified in mammalian tissues that are derived from neuroectoderm. Everywhere in tissues that house neuroectoderm-derived cells one should expect melanin and its derivative semiconductive atoms from group 2-4 to show up. This is why finding the leptin-melanocortin pathway changed my life. The central retinal pathways anterior to this tract are also filled with melanin as well.

Looking more closely in biology you’ll find melanin can be found mostly in the eyes, human skin, hair, inner ear, and even brain has a special melanin. Especially the midbrain where all sense and hypothalamic areas converge. It was identified to be black or brown depending on the composition and structural differences.

Skin is derived from neuroectoderm. So are your teeth. The color of your teeth tells me something. The color of your skin is called your Fitzpatrick type. It also tells me something.

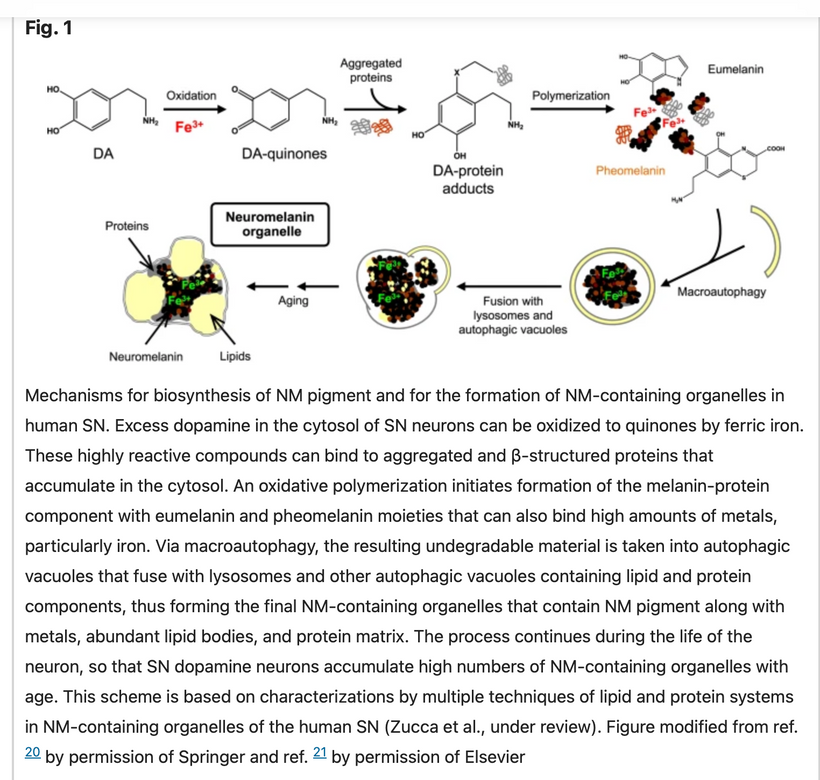

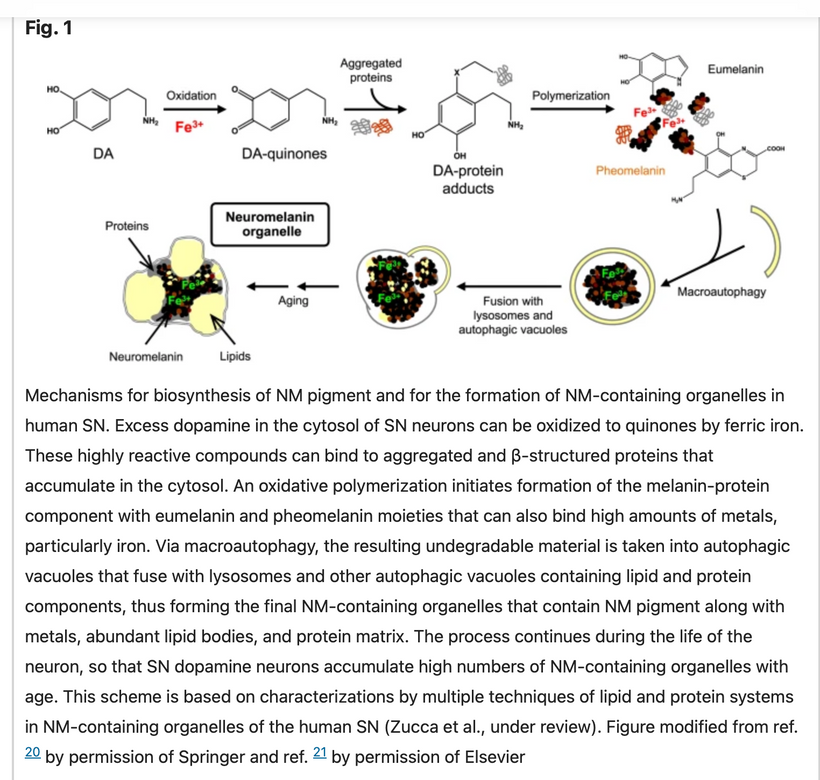

Melanin can either be eumelanin (with nitrogen attached between carbons) or pheomelanin (with sulfur attached between carbons) or neuromelanin (Prota, 1980).

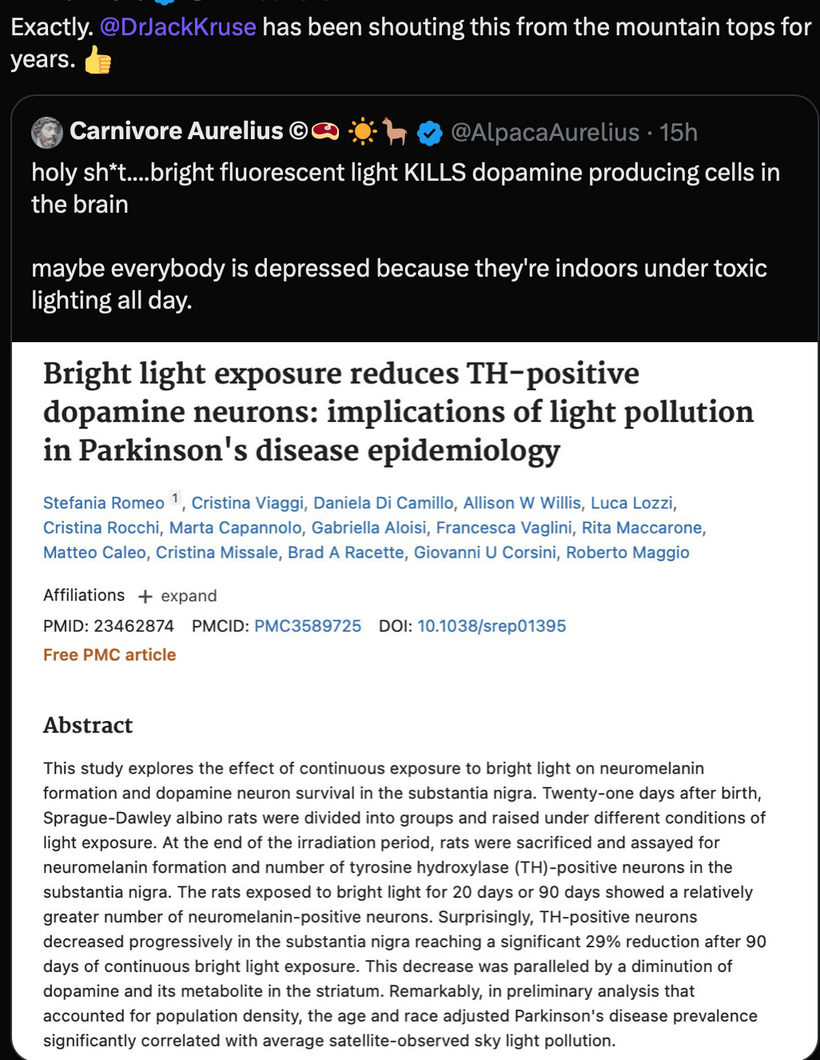

Neuromelanin (NM) is the darkest pigment found in humans. It is only located in the brain and it is structurally related to melanin. It is a polymer sheet of 5,6-dihydroxy indole monomers. Neuromelanin is found in large quantities in catecholaminergic (dopamine) cells of the substantia nigra pars compacta and locus coeruleus, giving a dark color to the structures.

Do you know why I mentioned it is the darkest human pigment in humans? That tells us something more about this semiconductive protein. The mechanism behind the color we perceive in semiconductors is fully explained by the band theory that governs color perception. Yes been color perception in a semiconductive event in humans.

If a pigment is able to absorb all wavelengths, we see it as black in the classical world. Color is an invisible coach to the decentralized mind. My friend Rick Rubin has been described as an invisible coach. When he had his own health issues he phoned me up and the advice I gave him was given in the classical world to help his ignorant surgeons at Stanford protect all the sound waves stored magnetically in the hydrogen lattice in his body. I view Ricks body as the master tape of the best music in the 20-21 century. I kept what I did for him quiet.

In this surgical situation, I was Rick’s visible coach who could explain the invisible magics in the advice I gave him. It turns out that what I told him to add to the surgeon’s recipe makes melanin a better wide-based semiconductor to protect the master tapes stored magnetically in his body. Below is Rick protecting those master tapes after his surgery. Note his eyes and the light around him.

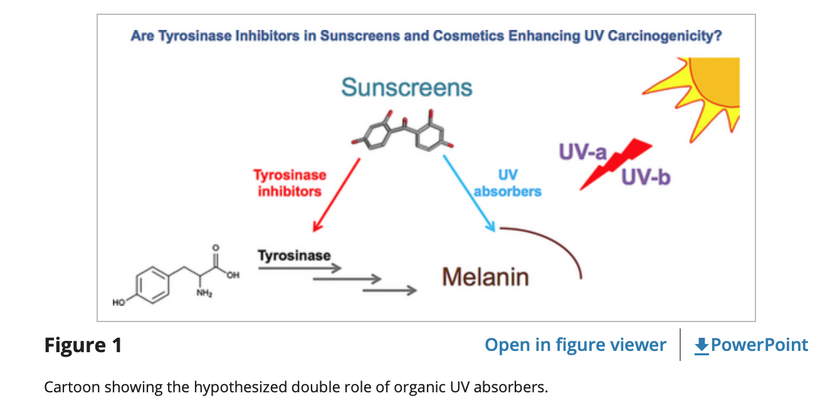

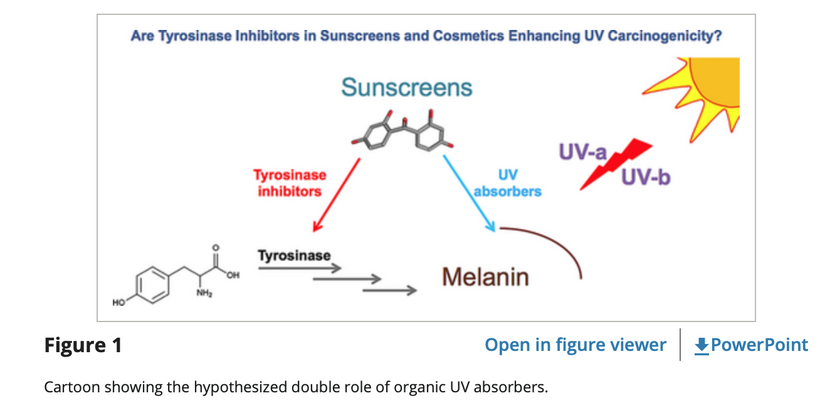

Back to the invisible magic to all centralized minds part of this story: Note the red ink below in Figure 1 below. Do you see how the iron oxidation state is specific in the reaction? Fe is at its +3 state. Why is this important?

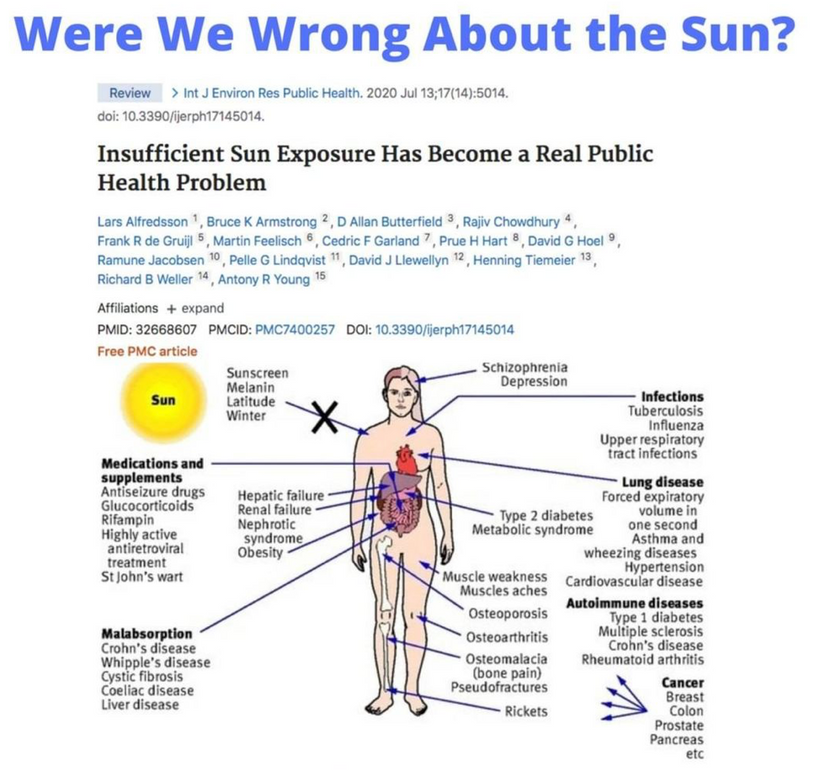

Your hemoglobin semiconductor protein refurbishes and regenerates your melanin semiconductor protein to work with full-spectrum sunlight. Your use of any sunscreen, sunglasses, contacts, and blue light or nnEMF blocks this refurbishing process and destroys melanin stores in your body.

Hemoglobin can bind 4 oxygen molecules. Iron changes its oxidation state when oxygen is bound from +2 to +3. Did you know that? Why?

The molecular orbitals in hemoglobin are different when oxygen is bound and when it is not bound, and this accounts for its color change: hemoglobin is red when oxygen is bound and blue when oxygen is not bound. This tells us that hemoglobin must also change its semiconductive band gap to account for the color change when its oxidation state changes.

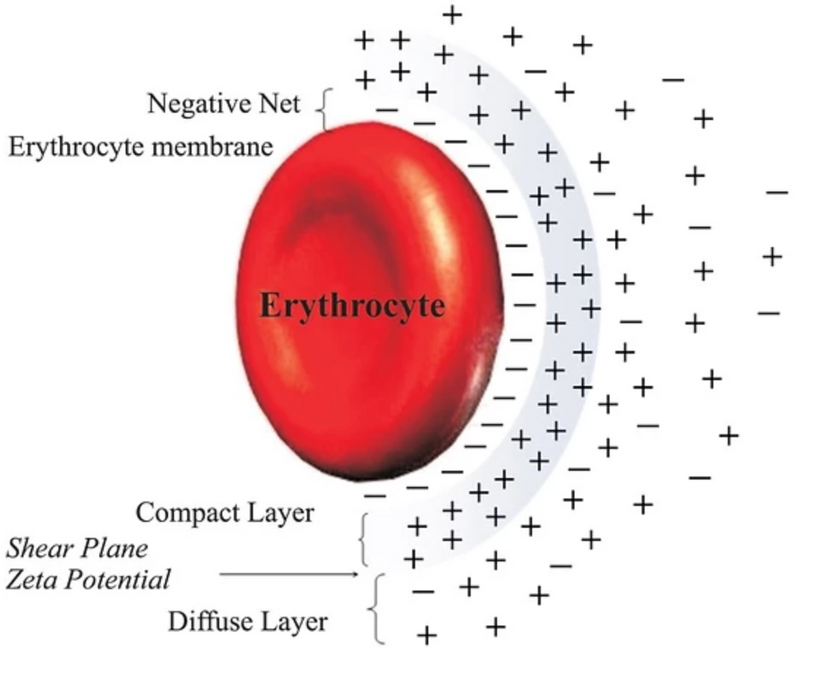

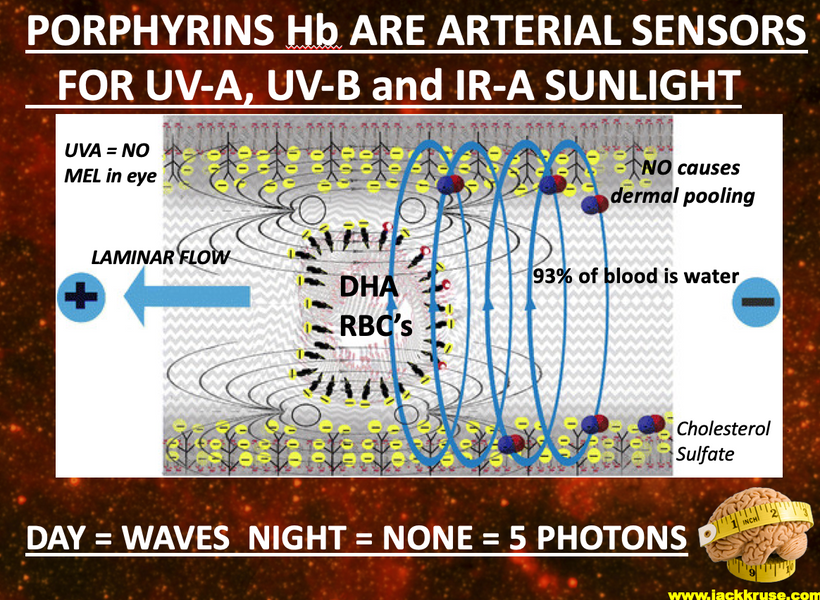

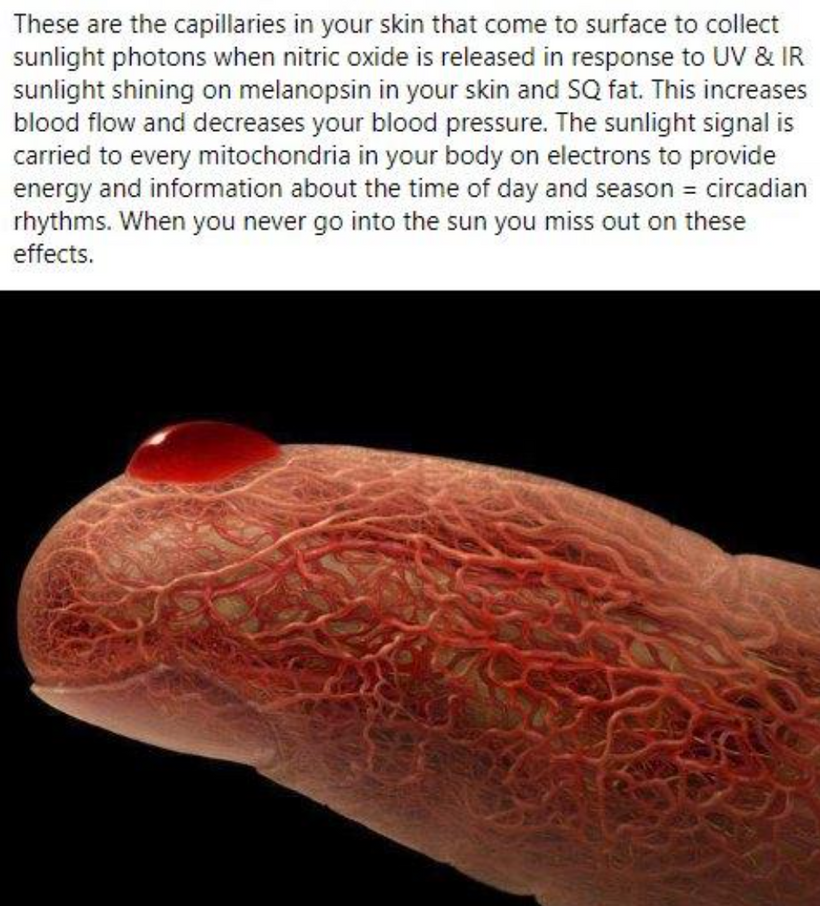

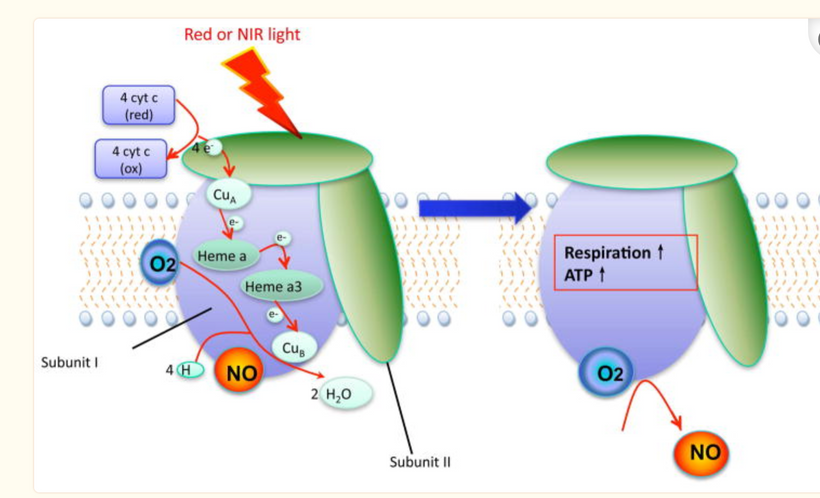

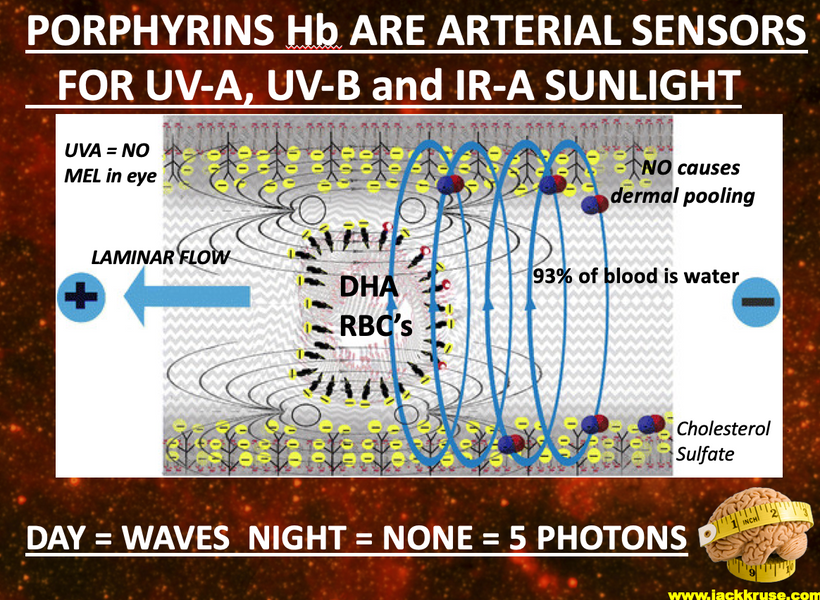

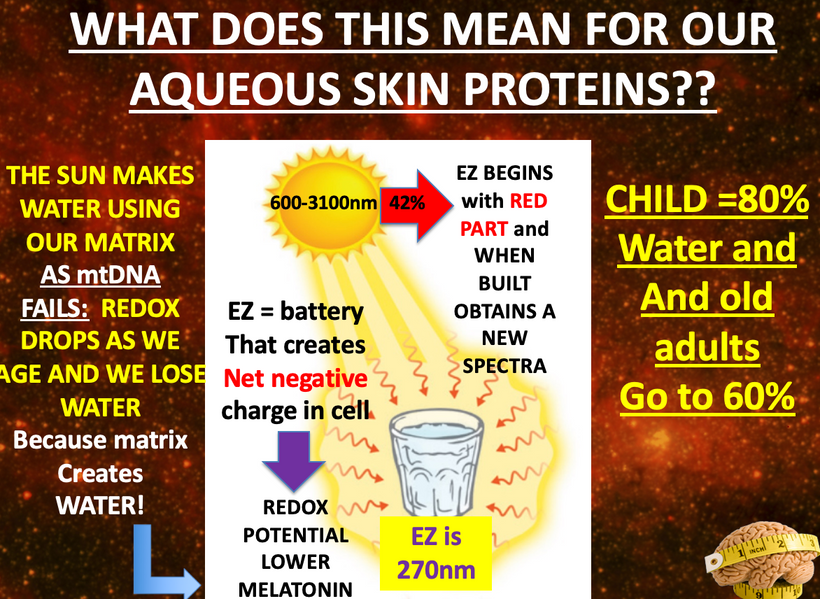

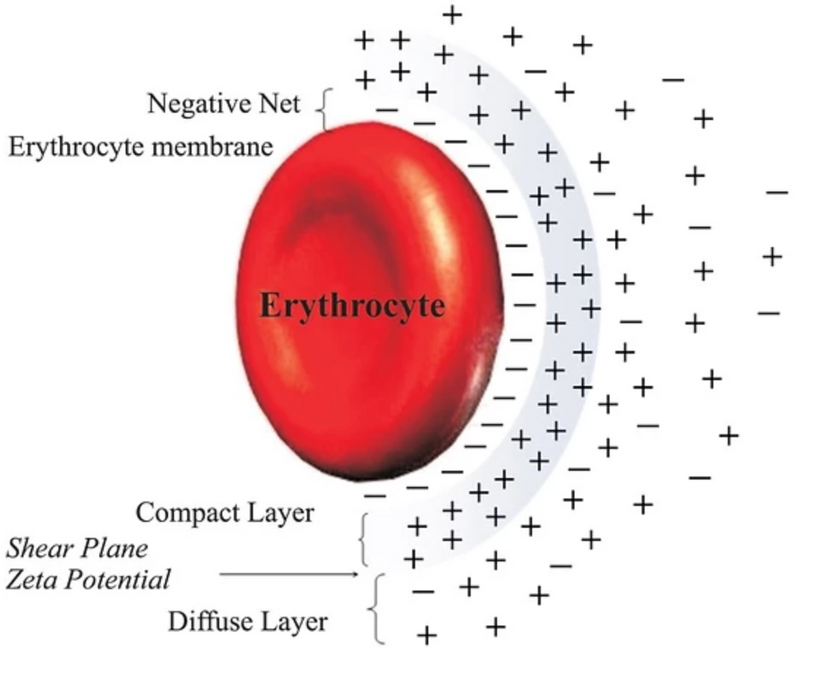

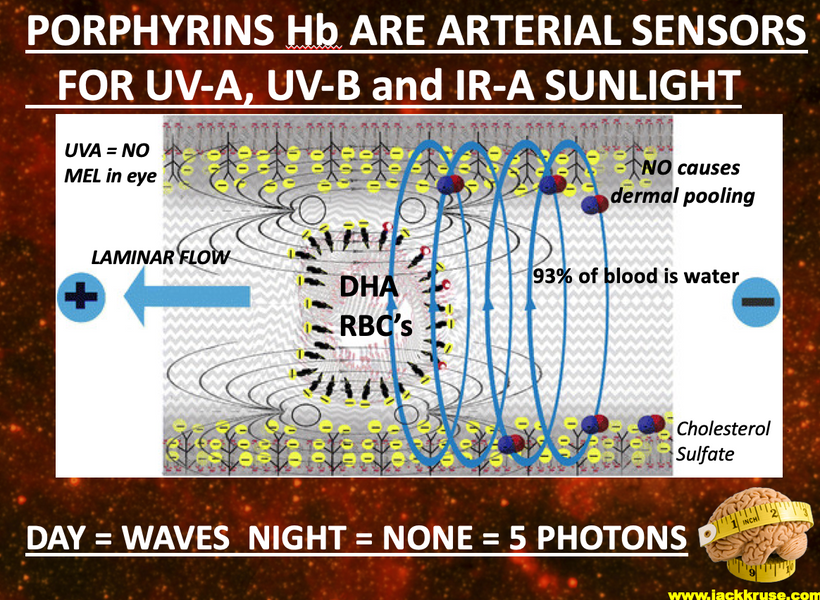

With hemoglobin there is an energy shift of 5 eV between deoxyhemoglobin and oxyhemoglobin and this large band gap emits UV light from hemoglobin (just like an LED diode does) into the blood plasma when this occurs. That plasma is filled with 93% water. Water undergoes a phase change and a charge change when it is irradiated by terrestrial sunlight as most of you know from my work. Blood takes on a net negative charge and this surrounds all the cells suspended in blood.

This includes platelets and it is the basis of the zeta potential in blood. This was a big deal for Rick’s surgery because of clotting risks (pic above).

When oxygen is not bound to hemoglobin, the iron atoms in its nitrogen cage are in the +2 oxidation state, and when it is bound to Hb in the Fe+3 state. The Fe+3 is more conductive electrically and this creates energy to improve the laminar flow of RBC in the blood vessels pictured above. At an atomic level, Fe+3 is slightly too big to fit into the hole in the center of the plane of the immediately-surrounding “heme,” so it rests just on top of the heme plane.

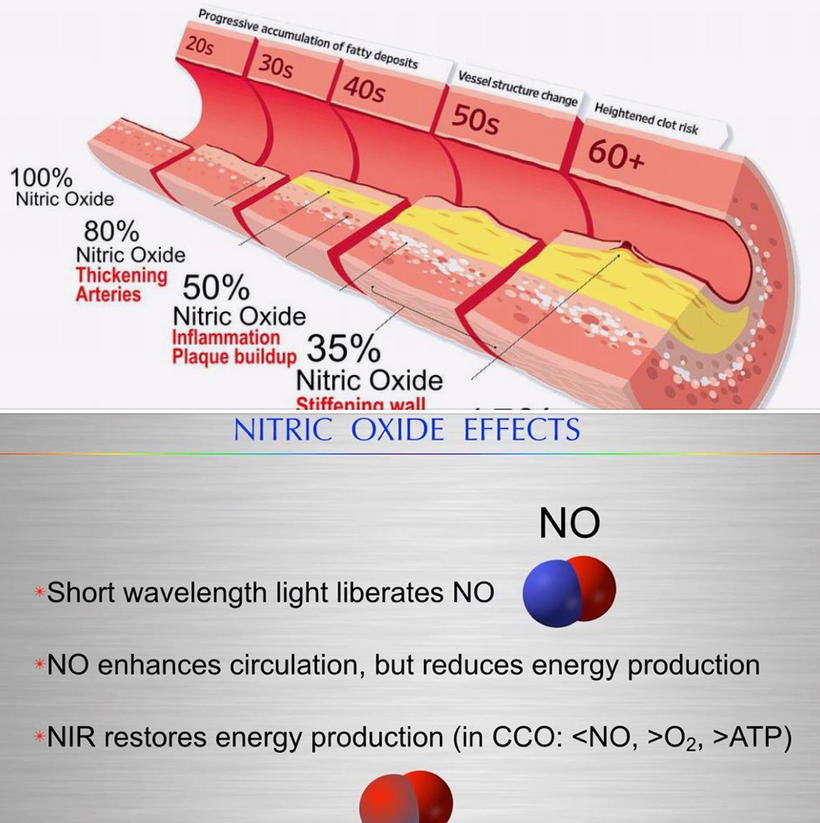

Did you know hemoglobin also binds and releases NO when a cell is hypoxic in and Fe is +2? This helps vasodilate blood vessels when they are hypoxic so that melanin can get more Fe in its +3 with oxygen.

I hope you remember that nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorus, and iron are also located in periods two and three in the periodic table of elements. This will become important soon in this story I am laying out to you.

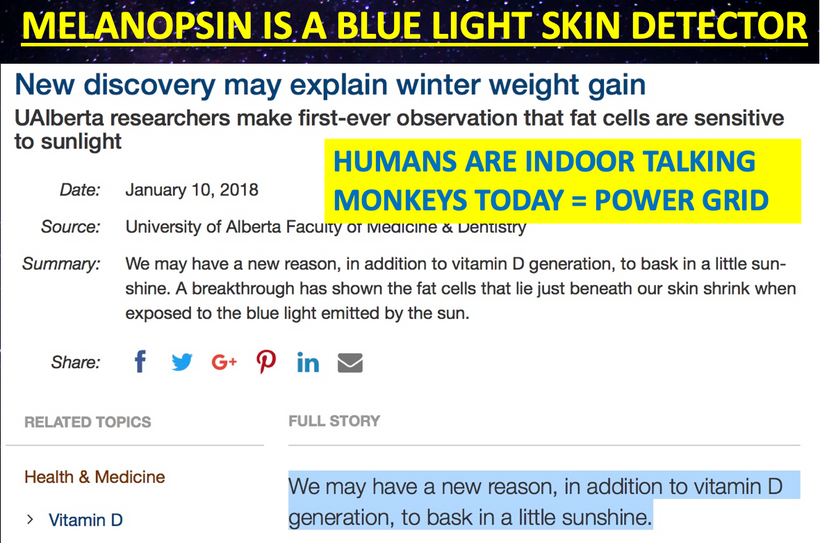

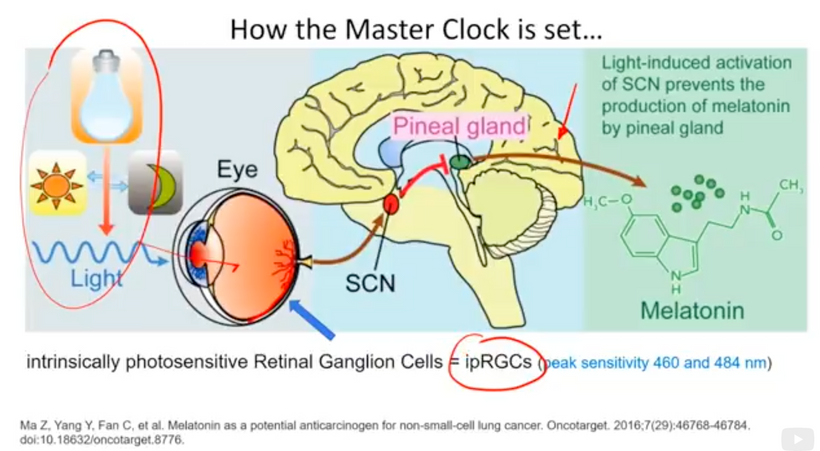

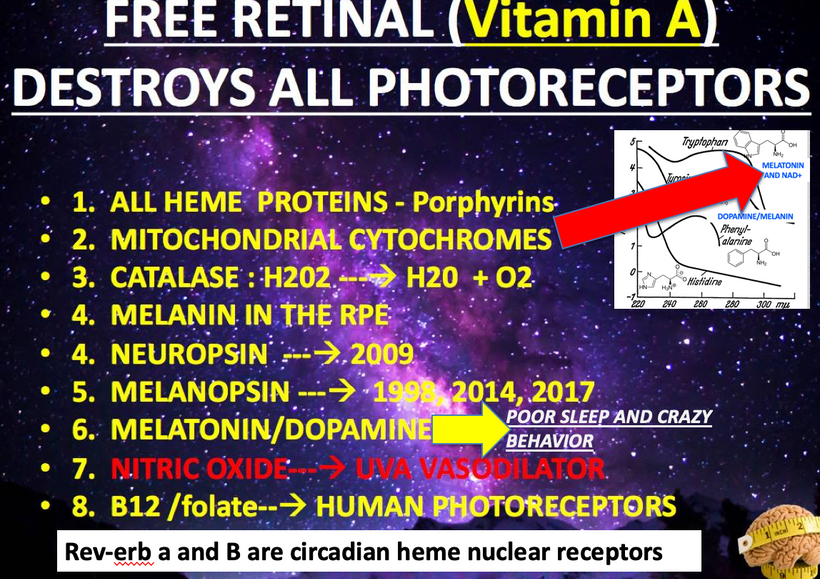

our photoreceptors in your eye all regenerate using two more semiconductive proteins called dopamine and melatonin. Both of them are created from aromatic amino acids that have very unusual absorption spectra of UV light.

Not only biologists, but melanin also attracted much of the attention of biophysicists due to the fact that apart from biological functions, melanin exhibits an interesting physical property such as high electrical conductivity leading to the suggestion that they could act as amorphous organic semiconductors (McGinness, 1972). Its threshold-switching behavior revealed that it can be used for electronic devices.

Melanin biology has even attracted the condensed matter people in physics because of its unique characteristics. The people in AI have no Earthly idea how this semiconductor is key to the human quantum computer in our skulls.

Due to its physical and biochemical behavior and its possibilities of combining amorphous semiconductors with that broadband monotonic absorption from UV-vis to NIR (Near Infrared). Also, it can be converted from photons into phonons (Meredith et al., 2006 below as cite #2).

Below is the graphic formulation of the periodic law, which states that the properties of the chemical elements exhibit an approximate periodic dependence on their atomic numbers. The table is divided into several areas called blocks. The rows of the table are called periods, and the columns are called groups. Elements from the same group of the periodic table show similar chemical characteristics. Trends run through the periodic table, with nonmetallic characters (keeping their own electrons) increasing from left to right across a period, and from down to up across a group, and metallic characters (surrendering electrons to other atoms) increasing in the opposite direction. The underlying reason for these trends is the electron configurations of atoms.

Cells use atoms from hydrogen to iodine on the periodic table. That is atomic number one to atomic number 53. Between atomic numbers, 1-53 many atoms are not used while the once that are used are often amplified. This fact should get the mitochondriac curious. Why would cells on the Earth do this? The answer is simple. Nature knew what the frequency of terrestrial sunlight was on Earth and that is why she built her semiconductive fabrication plant to take advantage of the band gap requirements of sunlight. When mammals faced a world devoid of UV light because of an asteroid strike melanin was created and amplified in that clade of animals. In ancient times, before the Cambrian explosion sunlight was the only source of energy with which we could run cells. This idea was stressed into cells at the KT event.

What is evolution really about? Energy, captured by semiconduction correctly can be applied to sculpt the atoms in cells to accomplish anything the environment can throw at it. This idea is very different that Darwin’s.

THE KT EVENT INTERRUPTED SUNLIGHT MUCH LIKE TODAY’S SUNSCREEN AND SUNGLASSES

Melanin is the main pigment found in mammals. It is responsible for the color of hair and fur. There are different types of melanin (eumelanin and pheomelanin), and they produce a huge color range, from black to sandy to red. A lion’s coloring is produced by melanin. Mammals were small and lived underground prior to the KT event. I covered this in detail in my book ten years ago. The reason is likely related to the semiconductors in their skin. Dinosaur and bird predators likely saw the UV spectrum.

All mammals and marsupials like the platypus and wombat have also been found to glow under ultraviolet (UV) light. This would have made them easy prey before the asteroid. It also explains why reptiles like dinosaurs likely only used melanin inside their tissues. Research has shown there was an intriguing evolutionary shift in the type of melanin used between cold-blooded and warm-blooded species found on Earth.

Birds and mammals contain significantly more of a sulfur-rich variant of melanin than amphibians and reptiles. This tells us their mitochondria density and capacity were different and it likely also explains why dinosaurs had small brains compared to their massive bodies.

This explains why these animals made it through the last extinction event. They were able to create their own UV light high bandwidth semiconductors internally and melanin inside of them captured this light for use physiologically. As time went on from the KT event, they amplified the ability to make melanin internally in their body plans and humans are the collateral effect of this happy accident for mammals.

Ancient mammals tend to be hairy according to the fossil record and so their colors are dictated by the pigments in their hairs. Eumelanins produce dark colors, while pheomelanins produce light colors. There is no such pigment that produces green color in the band gap color of melanin.

HYPERLINK

COLOR IS A SEMICONDUCTOR STORY

Physicists tend to see the world through a hydrogen/proton lens. Chemists tend to see the world through valence electrons.

A quantum biologist sees the world through how the protons and electrons and hydrogen act with iodine. These atoms are rearranged with specificity and sensitivity by sunlight to explain everything in biology on Earth. Melanin and hemoglobin are central to this developing story.

THE QUANTUM BIOLOGY LENS

Hydrogen should not be considered just a source of solar energy. Hydrogen is best thought of as a carrier of energy that cells favor in their mitochondria. Just as oil has grades telling us which is the more favored product so too does hydrogen. Light hydrogen is the favored carrier atom of solar energy for the semiconductive circuits of life.

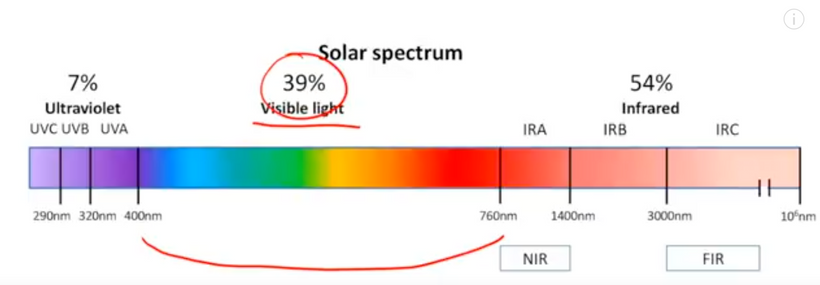

The heaviest atom used NORMALLY in human cells is iodine. No cell needs any other element past iodine. Why is iodine so damn important? It is large enough and has 7 valence electrons of electronegativity that it has enough electronegative power to draw hydrogen protons closer together to make the best performing wide band semiconductors in the UV to IR range of light using something called the Grothaus mechanism. Iodine can and should be thought of as our optical scissors in how we turn food into an electromagnetic signal for mitochondria to decipher. Recall that terrestrial sunlight we see goes between 250nm light and 760nm light.

The terrestrial solar spectrum actually is larger than we do not see between UV-C light at 250nm – 3100 nm light in the IR-C range. I’m sure you are now wondering what in the hell is a wide-band semiconductor.

Wide bandgap semiconductors have many useful characteristics, such as low permittivity, high breakdown potential of electric fields, good thermal conductivity, high electron saturation rates, and most importantly high radiation resistance. Yes, wide-band semiconductors actually protect electric currents from other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum that can destroy life.

Recall from the story above that for the first 3.8 billion years on Earth at times, the full complement of the electromagnetic spectrum has gotten through to different degrees at times and these frequencies could easily disorder AMO atomic arrangements in cells. Cells had to build plans to navigate this problem. Using a semiconductive design that favored radiation protection of the full spectrum of light from any star seems wise.

As a result of all these early conditions of existence on Earth, cells chose the atoms that could build semiconductors that spanned a conduction gap of 4.96 eV to 0.4 eV. Why were those numbers chosen? That is the band gap that corresponds to 250nm light and light up to 3100nm light. That is the thermodynamic range of the sun.

Hence, wide-band semiconductors can work at high temperatures found on Earth and are also ideal for developing semiconductor devices that have high frequency and power, and high temperature and radiation resistance. Taking group 3 nitrides as an example, in terms of optical properties, their optical band gap can vary continuously from 0.77 eV (InN) to 6.28 eV (AlN), completely covering the infrared to the ultraviolet band.

Since wide bandgap semiconductors can absorb and radiate high-energy photons, they are the most suitable candidates for fabricating blue, green, and other short wavelength light emitting diodes (LEDs), semiconductor lasers, and UV detector devices, which are widely used in the fields of optoelectronics and microelectronics.

SUMMARY

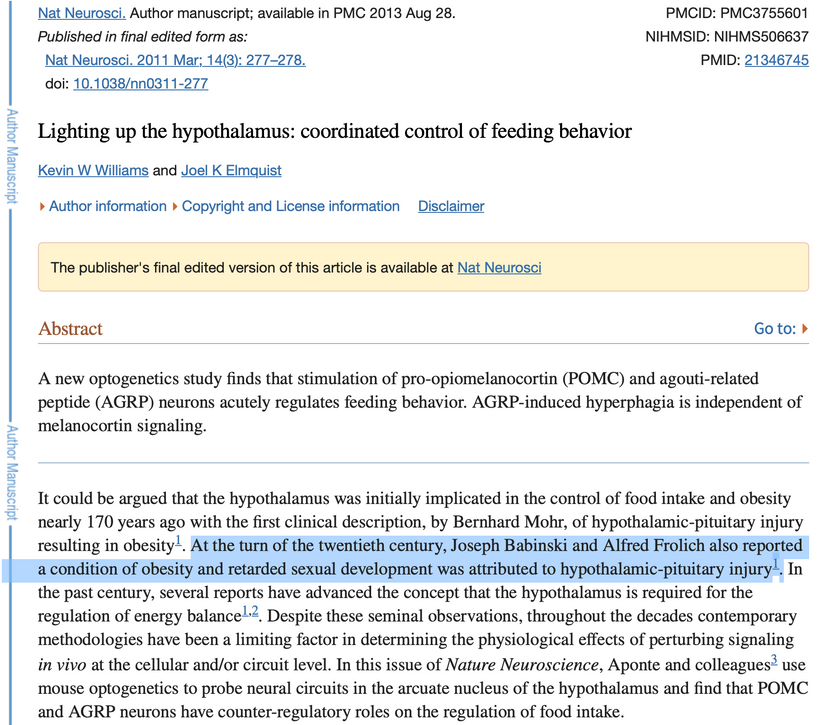

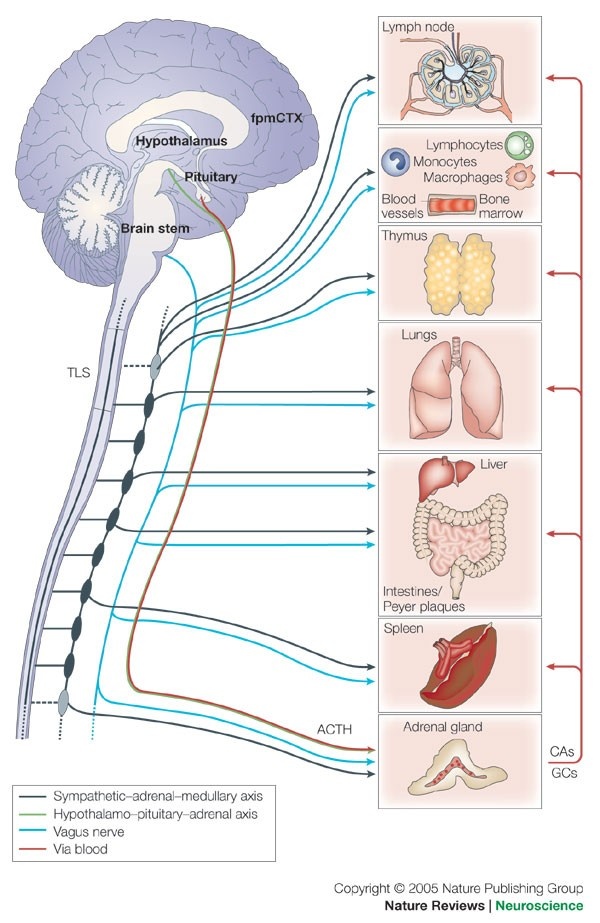

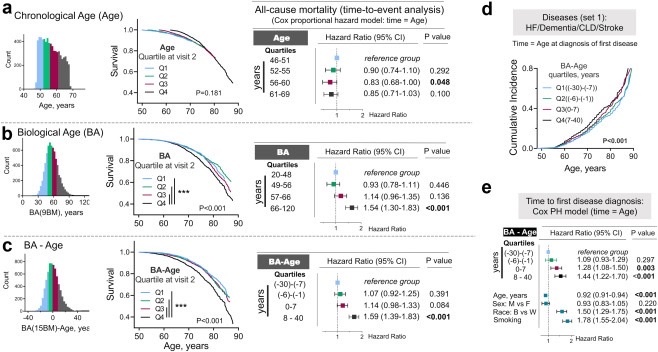

When oxygen drops, HIF 1 alpha is released and this affects the periodicity of the SCN and all peripheral clock genes. This is especially damaging in the case of hemoglobin and melanin semiconductors. Recall from the last blog that alpha MSH is made from sunlight via all our surfaces, skin, eyes, git, and brain. Alpha MSH is how we keep our melanin semiconductors from aging in the hypothalamus and midbrain. Controlling the oxidation state of iron in these proteins is key there and that links to the oxygen delivery system to melanin-containing semiconductors for reasons very detailed above.

How does it all tie together?

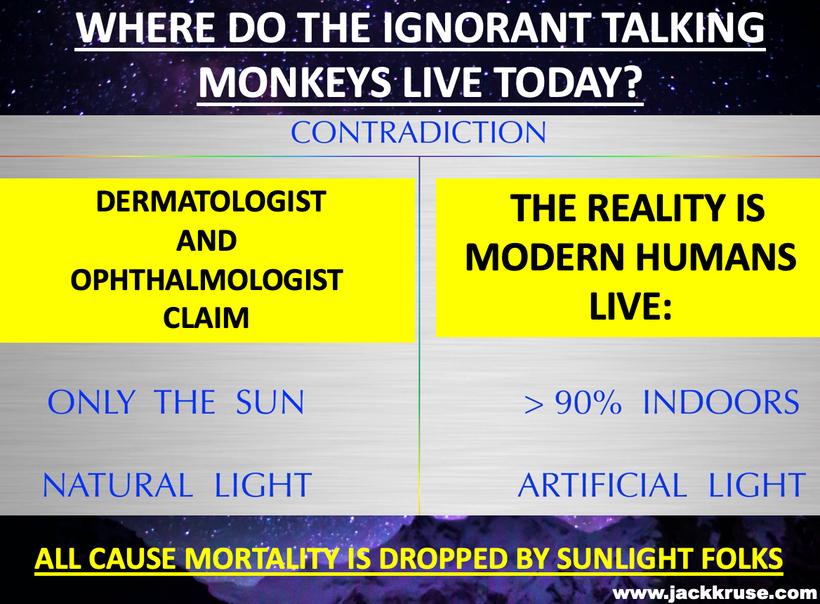

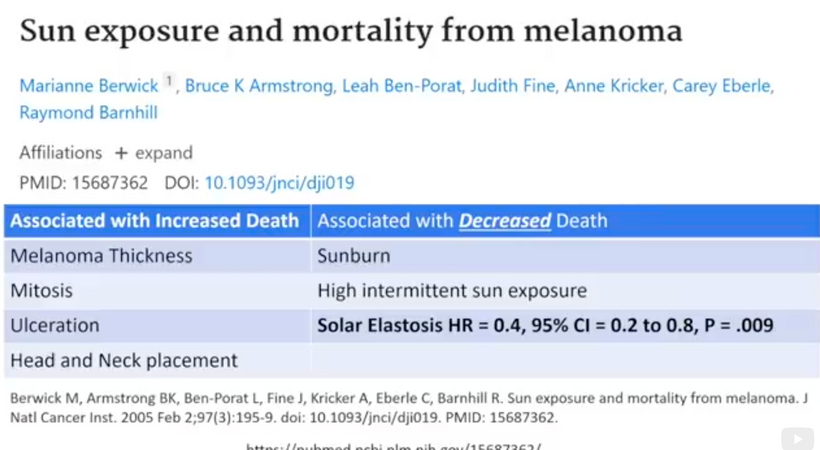

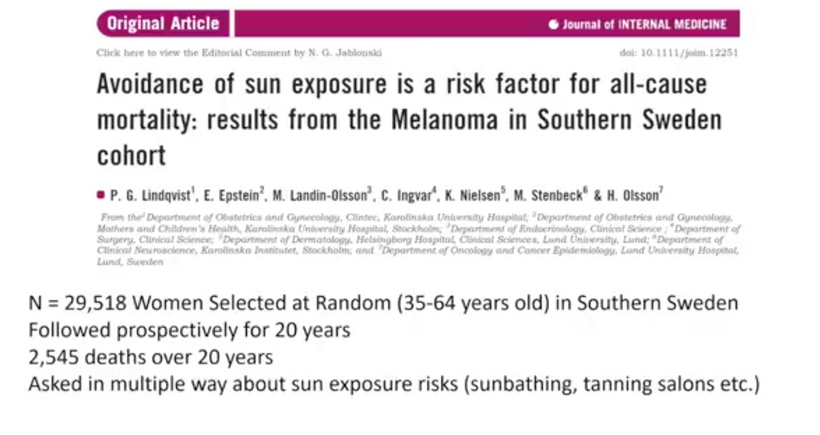

Today for the first time in my medical career there is overwhelming and compelling evidence that connects the circadian clock to many addictive behaviors and vice-versa, yet the functional mechanism behind this interaction remains largely unknown. You have just gotten that mechanism delivered to you for 5 bucks. Your job is to share it far and wide and show centralized clinicians and researchers just how myopic their thinking has been on this topic. It is the reason I have been pissed off and agitated at my profession for 20-plus years.

Your third eye is not an eye. It is your skin that has a massive array of melanin in it that powers the entire neuroectodermal layer of melanin everywhere in your body.

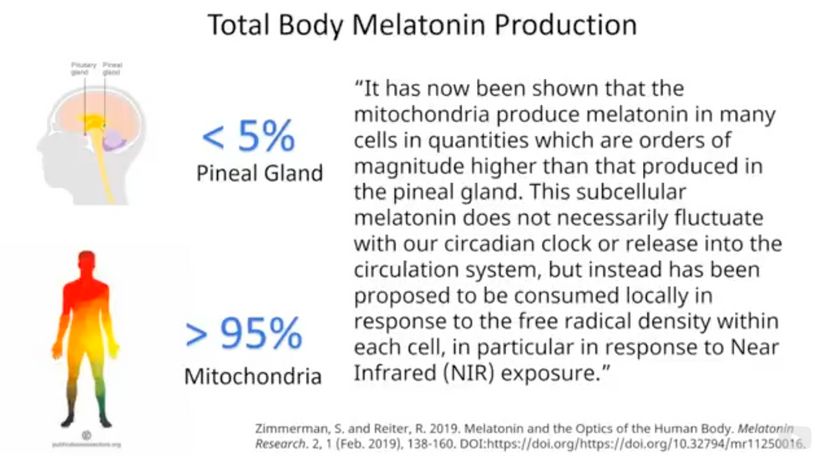

Melanin is destroyed by blue light and by nnEMF when it degrades. Iron in the wrong oxidation state powers its demise. Your melatonin and dopamine levels in your body are designed to help every heme-based semiconductor in your body to regenerate. It is your job to get out of these electromagnetic waves. You need to get into the sun which build melanin. Ivory Tower academics have ignored this science for far too long. 95% of this regenerative power is made in mitochondria. This is why the first step in heme synthesis of all wide-based semiconductors also begins in the mitochondrial matrix of MAN.

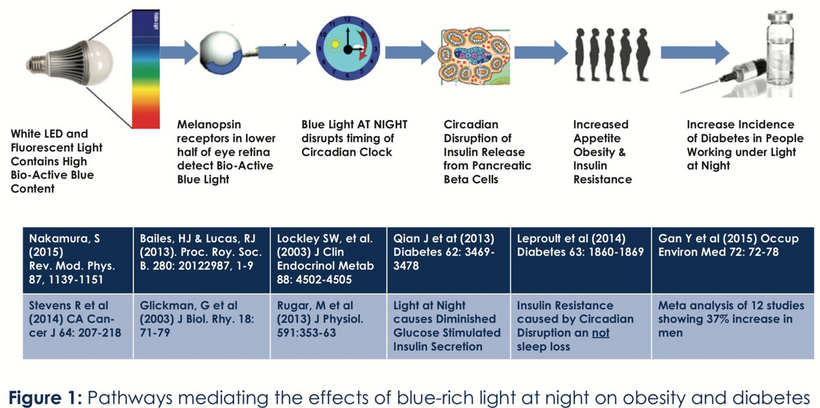

At the molecular level where most centralized researchers spend their time, multiple mechanisms have been proposed to link the circadian timing system to the addiction to sugar, food, drugs, gambling, supplements, and bad centralized advice. Low dopamine states are created by wide-based semiconductive demolition.

I can tell you even music has remnants of this effect. If you do not believe me listen to the tracks of Metallica and AC/DC. You’ll notice something profoundly different in both bands. The way in which the drums are used is ill-timed between the two groups. Guess why?

Do you know acoustic phonons are affected most by magnetic fields? True. Semiconductor science 101. Metallica’s musical heart is driven by their drummer, Lars Ulrich born in 1963 and his drum beats lead their music. He was into tennis, an outdoor sport until he migrated to the drums after he moved to Los Angeles at the 34 latitudes. Ulrich was born into an upper-middle-class family in Gentofte, Denmark. He was the son of Lone and tennis player Torben Ulrich. His paternal grandfather was tennis player Einer Ulrich.

In February 1973, Ulrich’s father obtained passes for five of his friends to a Deep Purple concert held in the same Copenhagen stadium as one of his tennis tournaments. When one of the friends could not go, they gave their ticket to the nine-year-old Lars and that is how his music career began. Lars Ulrich originally intended to follow in his father’s footsteps and play tennis outdoors, and he moved to Newport Beach, California, in the summer of 1980 as proof. Lars became known as a pioneer of fast thrash drum beats, featured on many of Metallica’s early songs because his dopamine level was supported by his early light environment.

AC/DC was driven by its guitarist, a heavy-smoking teetotaler.

AC/DC musical heart was Angus Young. His older brother is Malcolm a rhythm guitarist. What is the main difference between a modern rock band’s with drums and guitar? The way sound is amplified by nnEMF. Guitars >>>>Drums. The sound of drums also has a profound positive effect on the hydrogen bonds of water in how phonons are created. This in turn affects the dopamine created by melanin semiconductors in your brain and ear.

Organisms appear anti-entropic while alive. Not only do they keep the atomic organization of the semiconductors more intact, but also manage to have lots of energy for their activities = longevity. But how do they really manage their anti-entropic existence? What would a thermodynamic description of organisms be like?

Lars took better care of his wide-based semiconductive system better than Angus.

Angus was born in Australia in 1955. This should open the eyes of my members who are long-term readers. Oz is a natural geopathic stress zone and is infiltrated with more nnEMF than any land mass on Earth. in the late 1950s, he moved to Glasgow Scottland, latitude 55 North latitude. Young also learned how to fight on Cranhill’s tough streets at night and his family was prompted by a bad winter and TV advertisements offering assisted travel for families to immigrate back to Australia. So his family flew from Scotland to Sydney, Australia, in late June 1963. Do you think any of this was good for the melanin in his cochlea?

Young was 18 when he and his older brother Malcolm formed AC/DC in 1973. At 18 years old, his brain was not fully myelinated which meant the semiconductors in his neocortex were fully pounded by nnEMF and blue light his whole life. Bon Scott, their lead singer died of addiction = low dopamine state. Scott died from alcohol poisoning. In April 2014 Malcolm Young was forced to leave the band due to ill health due to alcoholism too. Do you know alcohol affects the oxidation state of iron in our body because of how it dehydrates us? Do you still think my hunches on semiconduction are wrong?

After Scott died they added Brian Johnson. AC/DC was set back with yet another departure; the new lead singer Brian Johnson was ordered by doctors to stop performing or face total hearing loss. Imagine that. See a trend yet? All this time AC/DC musical tracks have the drum beats of Phil Rudd behind the guitar tracks. Have you guessed why yet?

When your dopamine level is low chronically you experience time differently. This has been imprinted in their music from day one. In fact, it is also why the most common criticism of AC/DC is that their songs are excessively simple and formulaic. That is also linked to semiconductive degradation in the cochlea and brain. The health of their group has also shown these effects but I doubt one centralized MD put any of this together.

The molecular mechanism of the circadian clock consists of a transcriptional/translational feedback system linked to the melanin semiconductive proteins, with several regulatory loops. These loops are also intricately regulated by the wide-based semiconductors in us at the epigenetic level. Interestingly, the epigenetic landscape shows profound changes in the addictive brain, with significant alterations in histone modification, DNA methylation, and small regulatory RNAs. The combination of these two observations raises the possibility that epigenetic regulation is a common plot linking the circadian clocks with addiction and just about every other human behavior well. This is how a decentralized mind sees the world as very different than your centralized researcher or expert.

CITES

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5399705/

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1600-0749.2006.00345.x

Alaie Z., Mohammad Nejad S., Yousefi M.H. Recent advances in ultraviolet photodetectors. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2015;29:16–55.

Zhao S., Nguyen H.P.T., Kibria M.G., Mi Z. III-Nitride nanowire optoelectronics. Prog. Quantum Electron. 2015;44:14–68.

Ponce F.A., Bour D.P. Nitride-based semiconductors for blue and green light-emitting devices. Nature. 1997;386:351–359.

https://www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/living-with-blue-light-exposure

Pengfei T., Ahmad A., Erdan G., Ian M.W., Martin D.D., Ran L. Aging characteristics of blue InGaN micro-light emitting diodes at an extremely high current density of 3.5 kA cm−2. Semicond. Sci. Technol.