The poem above was written for me by Anna P., a college freshman at Spring Hill University in Mobile Alabama..

There’s a reason why the first thing we often ask someone when we meet them, right after we learn their name, is “where’s home for you?”

For me home is 100% in Nature. It does not require a house for me. This makes my perspective unique in the West.

We may use our homes to help distinguish ourselves, but the dominant Western viewpoint is that regardless of location, the individual remains unchanged. It wasn’t until I stumbled across the following notion, mentioned in passing in a book about a Hindu pilgrimage by William S. Sax, that I began to question that idea: People and the places where they reside are engaged in a continuing set of exchanges; they have determinate, mutual effects upon each other because they are part of a single, interactive system.

What I learned from Eastern philosophy is that while in the West we may feel sentimental or nostalgic attachment to the places we’ve lived, in the end we see them as separate from our inner selves. Most Westerners believe that your psychology, and your consciousness and your subjectivity don’t really depend on the place where you live, They come from inside — from inside your brain, or inside your soul or inside your personality. But for many Eastern cultures, a home isn’t just where you are, it’s who you are.

I realized I am relentless chaos years ago. That is where my home is built.

In the modern Western world, perceptions of home are consistently colored by factors of economy and choice. There’s an expectation in our society that you’ll grow up, buy a house, get a mortgage, and jump through all the financial hoops that home ownership entails.

The endless options can leave us constantly wondering if there isn’t some place with better schools, a better neighborhood, more green space, and on and on. We may leave a pretty good thing behind, hoping that the next place will be even more desirable.

In some ways, this mobility has become part of the natural course of a life for this Black Swan. The script is a familiar one: you move out of your parents’ house, maybe go to college, get a place of your own, get a bigger house when you have kids, then a smaller one when the kids move out. It’s not necessarily a bad thing. Even if we did stay in one place, it’s unlikely we would ever have the same deep attachment to our environment as those from some South Asian communities do. It just doesn’t fit with our culture.

But in spite of everything — in spite of the mobility, the individualism, and the economy — on some level we do recognize the importance of place. The first thing we ask someone when we meet them, after their name, is where they are from, or the much more interestingly-phrased “where’s home for you?” We ask, not just to place a pushpin for them in our mental map of acquaintances, but because we recognize that the answer tells us something important about them. My answer for “where are you from?” is usually NYC, but “where’s home for you?” is a little harder for me to answer because I do not resonate with the concrete jungle any longer.

That environment taught me what not to seek in a home.

Home is where my heart beats well in Nature, then by its most literal definition, my home is wherever I am at that moment. I make the best of it because I a confident that I am making the choices of where I should be living for me.

Home is where I have all my skin in my own game.

And the truth is, the location of your heart, as well as the rest of your body, does affect who you are. The differences may seem trivial (a new subculture means new friends, more open spaces make you want to go outside more), but they can lead to lifestyle changes that are significant.

Memories, too, are cued by the physical environment we choose these days. We remain clueless about how the nnEMF footprint changes our feelings about the place we live now. When you visit a place you used to live and feel the difference now, these cues can cause you to revert back to the person you were when you lived there. You realize for the first time just how relative time is.

The rest of the time, different places are kept largely separated in our minds. The more connections our brain makes to something, the more likely our everyday thoughts are to lead us there. But connections made in one place can be isolated from those made in another, so we may not think as often about things that happened for the few months we lived someplace else. Looking back, many of my homes feel more like places borrowed than places possessed, and while I sometimes sift through mental souvenirs of my time there, in the scope of a lifetime, I was only a tourist in my own journey.

I can’t possibly live everywhere I once labeled home, but I can frame these places on my walls. My decorations can serve as a reminder of the more adventurous person I was in New York City, the more carefree person I was in Connecticut, and the more ambitious person I was in New Orleans. I can’t be connected with my home in the intense way Easterns are, but neither do I presume my personality to be context-free. No one is ever free from their social or physical environment. This is ever more true in todays social media terroir. And whether or not we are always aware of it, a home is a home because it blurs the line between the self and the surroundings, and challenges the line we try to draw between who we are and where we are.

For me right now as a soloist, home isn’t a place. It is a person. And I think I am finally getting home right.

I live in my own little world. But its ok for me. It appears they know me here well and I like that discomfort.

Reading Anna’s poem made me realize discomfort is the price of admission to a meaningful life………….I rather like that.

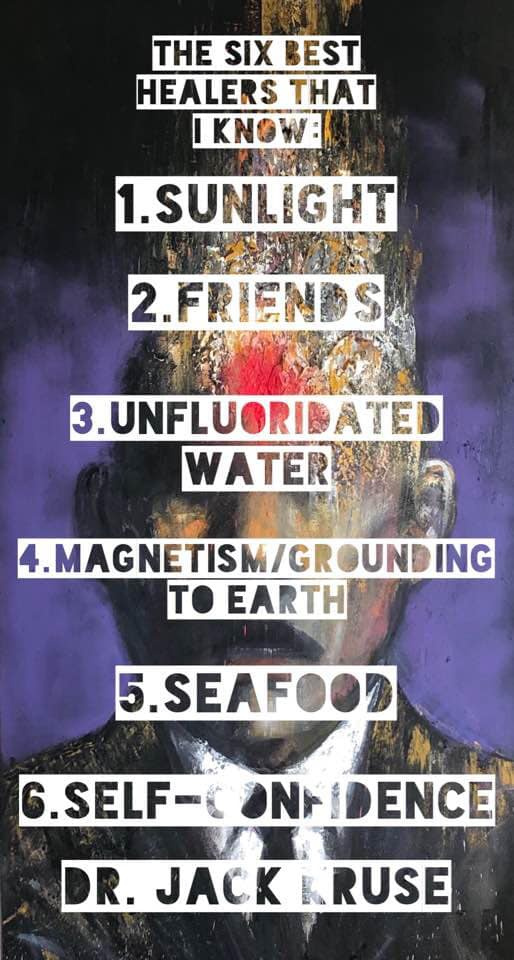

Your friends and family might not understand your new found ideas so this might help you help them to improve your relationships with in your circle of six.

Your friends and family might not understand your new found ideas so this might help you help them to improve your relationships with in your circle of six.